Summary

AI systems can produce individually novel outputs, but novelty alone is not creativity. We argue that genuine creativity requires respect for constraints—the accumulated structure of prior discoveries—and that current AI systems lack this capacity because their training takes greedy paths that preclude the right kind of representations. Constraints operate at three levels: physical (baked into matter), concrete (instantiated in a fixed substrate), and modelled (represented so they can be manipulated, transferred, and counterfactually varied). Understanding—the cognitive form of this third level—is the capacity to navigate between constrained perspectives and integrate across them. LLMs are convincingly coherent within any single frame, but they possess no trajectory of their own; their aggregated voice resolves into a coherent perspective only when a human supplies the grounding. The most promising path is human-AI co-creativity, but we leave the door open for any system—biological or artificial—whose learned, factored, path-dependent representations let it extend its own phylogeny.

Why Creativity Cannot Be Interpolated

And Why Understanding Is the Path to Get There

“To understand human-level intelligence, we are going to need to understand creativity. It’s a big part

of what being intelligent means from a human level, is our creative aspect.”

— Kenneth Stanley, On Creativity, Objectives, and Open-Endedness – HLAI Keynote

What are sparks without a fire? The authors of the GPT-4 technical report proclaimed “sparks of AGI”, but a fire was, and is still, nowhere to be found. Despite apparent recent breakthroughs, AI on its own is missing the fire of creative power. And without this fire, AI will never venture beyond the territory it was trained on. As Neuroevolution: Harnessing Creativity in AI Agent Design puts it: “While [neural networks] interpolate well within the space of their training, they do not extrapolate well outside it”. By “interpolation” we mean something broader than the mathematical sense: recombination within existing conceptual structure. A system that interpolates may produce individually novel outputs—new sentences, new images—but only by averaging what it has seen, without representing the domain’s actual structure. Creativity, by contrast, respects that structure—the constraints of a domain—well enough to extend it, opening up genuinely new dimensions in the space of possibilities.

Creativity is not random. Many people picture it as chaotic—throw enough paint at the wall and eventually you get a Pollock. But it is more like fitting puzzle pieces together for a puzzle that never existed—the pieces must still interlock, even as you invent the picture. Yes, there is serendipity. But the stumbling happens along paths carved by structure, not by chance.

We want AIs that can “think”, but what is thinking? Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman’s 2011 bestseller Thinking, Fast and Slow (Kahneman 2011) divides thinking into two systems.1 “System 1” thinking is fast, intuitive, and instinctive. It can make effective judgements when grounded in experience, but it operates within familiar territory. System 1 is what current AI systems do well: rapid pattern matching within their training distribution. But pattern matching fails when the territory is genuinely new. Every domain we care about—writing code, driving cars, doing science, counselling patients—demands handling unknown unknowns: situations no training set anticipated. As we shall see, more intelligence can paradoxically make this harder, not easier.

“System 2” thinking is slow and deliberate, and is epitomised by reasoning. Unlike System 1, reasoning can venture into unfamiliar terrain by breaking the unknown into familiar pieces, constrained by the logic of what must fit together. This is the constraint-respecting mode of thought: not free association, but structured exploration where each step must cohere with what came before.

For an AI to “reason”, then, it must engage in some kind of deliberate, structured, compositional process that is aimed at acquiring knowledge and understanding. Not reasoning is very different from reasoning poorly. For example, if you ask me to find the best move in a chess position, I might make lots of mistakes in my analysis and miss the best move, yet still be reasoning. By contrast, Magnus Carlsen might “see” the best move instantly, without doing any explicit reasoning. Thus, whether one is reasoning is neither determined by the task one is performing nor the quality of knowledge one acquires—a non-reasoner may acquire better knowledge—but by the process one is using.

We do not acquire knowledge in a vacuum. You don’t really understand physics right after a lecture, or even after a degree—you understand it after doing the exercises, after years of reflection, building bridges to your own experience.2 Understanding is less “acquired” than it is synthesised and constructed.

Human understanding can be asymmetric: we often grasp things in a discriminative way that we cannot articulate generatively. This is what we call taste—an ineffable sense of what works, even when we cannot say why or produce it on demand. Human creatives working in complex, ambiguous domains exploit this asymmetry: they generate many candidates and then discriminate, using their superior taste to select the better paths. Over time, this becomes self-adversarial—each round of discrimination sharpens the generator, raising the bar for what taste will accept next.

Current AI systems suffer from a far more extreme asymmetry. They can often recognise good solutions, yet generate mediocrity—partly because generation requires the deep structural knowledge that constrains the search, while verification can lean on shallower pattern matching; partly because discrimination focuses a model’s full capacity on a single judgement, while generation disperses it across the output space, representations, and context with a fixed computational budget per step. As we shall see, much recent progress has come from adding external constraints, but the understanding those constraints embody comes from outside the system, not from within. Humans too use constraints to navigate domains that exceed their generative grasp—the difference is that our taste is far richer, so we can provide our own scaffolding.

But intelligent reasoning is not simply applying a deliberate, structured, compositional process. A calculator applies such a process, and might produce in you the new knowledge that 127,763 * 44,554 = 5,692,352,702 (aren’t you glad). Yet a calculator is hardly intelligent. More is needed, and we will argue that what separates robust generalisation from brittle skill is something that looks a lot like creativity—the capacity to respect and extend the structure of what came before.

1 Intelligent reasoning needs creativity (but not vice versa)

Why “but not vice versa”? Because creativity does not need intelligence. Evolution produced the entire tree of life through blind variation and selective retention, with no intelligence at all. Daniel Dennett had a name for this: competence without comprehension Dennett 2017. Competence Without Comprehension

One of Darwin’s 19th-century critics captured the idea perfectly, albeit in outrage: Darwin, “by a strange inversion of reasoning, [he] seems to think Absolute Ignorance fully qualified to take the place of Absolute Wisdom in all of the achievements of creative skill” Dennett 2009. As Dennett loved to point out: that’s exactly right. The eagle’s wing, the dolphin’s fin, the human eye—all designed by a process with no insight, no purpose, no mind at all. Turing stumbled on the same strange inversion: a computing machine need not know what arithmetic is to perform it perfectly. Both showed that competence bubbles up from below: “understanding itself is a product of competence, not the other way around”. We “intelligent designers” are among the effects of this process, not its cause.

But evolution still has constraints—physical and concrete, baked into the laws of nature and matter itself, rather than modelled in representations that can be manipulated, transferred, and varied. How creativity can operate through such constraints without understanding is a tension we will resolve through our analysis of AlphaGo and the hierarchy of constraint adherence.

1.1 Chollet and “strong” reasoning

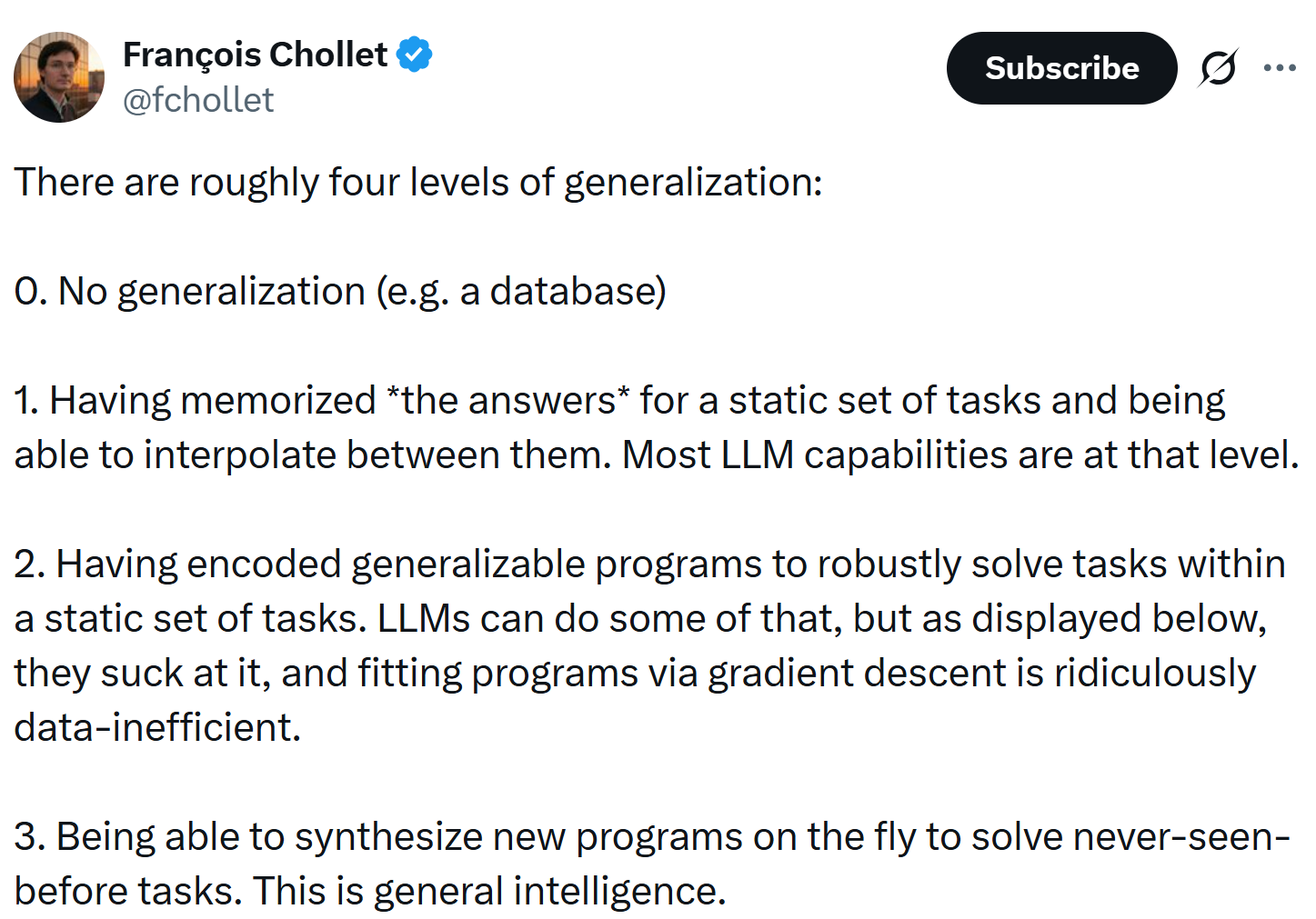

In 2019, Keras author François Chollet proposed a framework for measuring intelligence, focusing on generalisation as the key idea.

Generalisation requires more than skill—the ability to perform a static set of tasks. A calculator is all skill; it can only do what it was hard-wired to do. Generalisation requires the capacity to acquire capacity, on-the-fly in response to new challenges. Chollet defines intelligence as:

“The intelligence of a system is a measure of its skill-acquisition efficiency over a scope of tasks, with respect to priors, experience, and generalization difficulty.”

Chollet has more recently called this “fluid intelligence”. Note that this measure is relative to a scope of tasks; Chollet rejects the idea of universal intelligence, in stark contrast to folks like Legg and Hutter who think a single dimension of intelligence could rank humans, animals, AIs, and aliens alike.

To summarise, in Chollet’s own words, general intelligence is “being able to synthesise new programs on the fly to solve never-seen-before tasks”. Chollet gives a spectrum of generalisation: local generalisation handles known unknowns within a single task; broad generalisation handles unknown unknowns across related tasks; and extreme generalisation handles entirely novel tasks across wide domains. The late cognitive scientist Margaret Boden—whose typology of creativity we will develop in Section 2—drew an influential distinction between exploratory creativity (finding new solutions within an existing framework) and transformational creativity (reshaping the framework itself). In her terms, Chollet’s intelligence is a powerful form of exploratory creativity. Chollet would argue that this covers broad and even extreme generalisation—but as we will see, his framework bounds these within fixed priors. Genuinely unknown-unknown territory requires transformational creativity: the capacity to extend or reshape the space of possibilities.

Chollet does use the term “unknown unknowns” for his broader generalisation levels, yet his framework bounds them in two ways. First, he assumes that human-like general intelligence shares our innate Core Knowledge priors—basic cognitive capacities like objectness, agentness, number, and geometry—arguing that these priors “are not a limitation to our generalisation capabilities; to the contrary, they are their source”. Second, he explicitly limits scope to “human-centric extreme generalisation...the space of tasks and domains that fit within the human experience”. These two bounds are related: as Chollet himself writes, priors “determine what categories of skills we can acquire”—he sees this as enabling (the No Free Lunch theorem means you need assumptions to learn at all), but it also means the “wide domains” of extreme generalisation are still those that Core Knowledge lets you make sense of.

Chollet’s “unknown unknowns” are novel combinations within this prior-bounded space, not paradigmatically new discoveries that expand the space itself. Evolution produced Core Knowledge priors in the first place—that is the meta-level creativity Chollet’s framework cannot account for. His measure presupposes the priors; it cannot explain their origin. Chollet himself is candid about this: “the exact nature of innate human prior knowledge is still an open problem” (Chollet 2019).

Three claims are in play: Core Knowledge (Spelke and Kinzler 2007) is psychological (innate capacities for objectness, agentness, number, geometry); Chollet’s measure is epistemological (skill-acquisition efficiency given those priors); his “kaleidoscope hypothesis” is ontological (reality itself is built from recurring patterns). Philosopher Mazviita Chirimuuta identifies this last claim as recognisably Platonic (Chirimuuta 2024). The position echoes Chomsky’s rationalism (Chomsky 2023): both treat intelligence as exploration within fixed innate priors, and remain silent about where those priors came from. Chirimuuta’s Kantian counter: the patterns may be “demands of human reason” rather than discoverables (Chirimuuta 2024)—in which case, the benchmark measures fitness to a particular model of mind.

This matters for creativity. If Chollet’s priors are the bedrock of cognition, the distinction between exploratory and transformational creativity collapses—all creativity becomes exploration within a fixed space. Our position requires that priors are contingent: evolved, path-dependent, and in principle revisable—shaped by the same meta-level process that Chollet’s framework cannot account for.

We do not need to settle these questions here. What matters is what Chollet gets right. His core insight—that general intelligence amounts to on-the-fly program synthesis—has proved highly productive. The ARC Prize competition, built around his benchmark, has drawn thousands of participants (Chollet, Knoop, and Kamradt 2025), and Chollet has since founded ndea, a research lab dedicated to combining program synthesis with deep learning. Much of this article owes its framing to Chollet’s thinking.

Where we extend Chollet is in asking how a system builds the internal structure that makes program synthesis possible. Chollet’s framework measures skill-acquisition efficiency and screens off internal mechanism from the description. Unfortunately, that means that a system can score well on capability benchmarks and still lack anything we would recognise as understanding. As we saw above, synthesis is deeply linked to how we acquire knowledge and understanding. We will call this process of composing models on the fly (to handle novelty) strong reasoning, to distinguish it from the meagre processes used by the likes of a calculator. Understanding how a system builds the internal structure that makes such composition possible is one of the central questions of this article.

1.2 Stanley and the need for open-endedness

A key architectural omission from Chollet’s account is the notion of agency. When Tim interviewed him in 2024, he expressed a strong interest in exploring the topic more deeply but said (after the interview) that he didn’t yet have a “crisp” way to do so. Curiously, the third version of Chollet’s ARC-AGI benchmark has been designed to target “exploration, goal-setting, and interactive planning”, which Chollet considers to be “beyond fluid intelligence”.

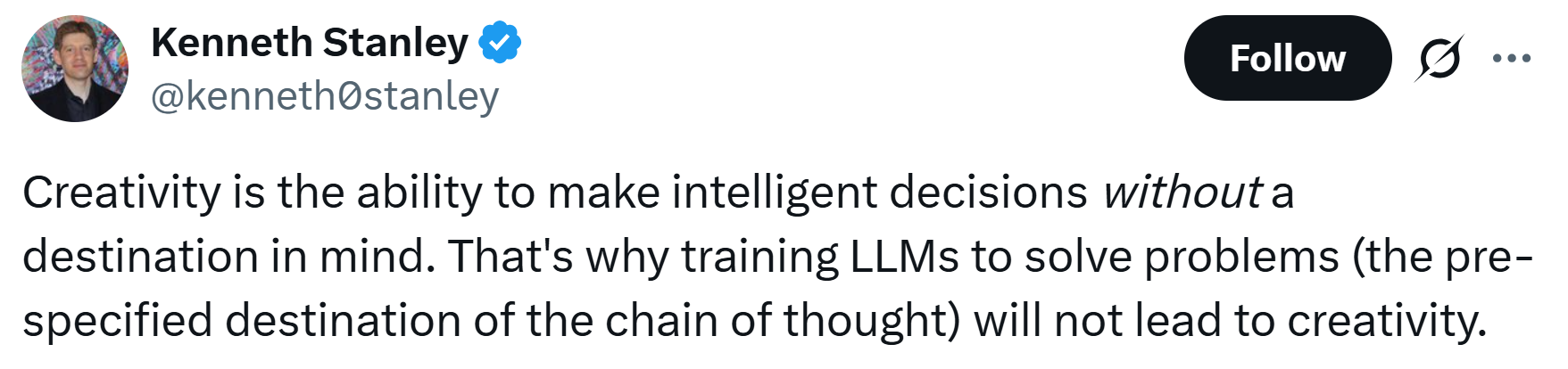

But computer scientist Kenneth Stanley, author of Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned and one of the deepest thinkers about AI creativity, sees things differently. His book deliberately avoided defining intelligence—its target was the tyranny of objectives, the very paradigm that Chollet’s task-solving measure exemplifies. In later work, Stanley argued that “it was open-ended evolution in nature that designed our intellects the first time” (Stanley 2019), and in our interviews he has described creativity as “a big part of what being intelligent means at the human level” (Stanley 2021). Where Chollet treats exploration and goal-setting as beyond the scope of his benchmark, Stanley sees them as the heart of the problem.

There is a deeper connection here. Agency is goal-directed by definition: it takes actions to achieve goals. Intelligence, in Chollet’s sense, is about how efficiently you learn given priors and experience, not about what you are searching for. But Chollet’s picture of intelligence is still deployed toward objectives: you acquire skills in order to solve tasks. So both share the same vulnerability when those objectives are misspecified. When the objective is what Stanley calls a “false compass”, both become blinkers—focusing attention on the goal while missing the stepping stones that don’t resemble it. More intelligence or more agency just means charging faster in the wrong direction, efficiently acquiring the wrong skills. Intelligence and agency only help if you happen to be solving the right problem or moving toward the right goal—they are tools for exploratory creativity, not transformational creativity. But when the objective is genuine—when constraints have accumulated and the problem is well-defined—intelligence can actually help you. The more knowledge and structure you bring to a task, the more efficiently intelligence can exploit it. This is why Chollet’s measure includes “priors” and “experience”: intelligence leverages what you already have.

Stanley argues that convergent, goal-directed thinking limits the imagination; that divergent thinking is required to discover knowledge of unknown unknowns. Paradoxically, Stanley argues, this open-endedness is also essential for solving complex tasks. Complex and/or ambitious tasks are “deceptive”; which is to say that (some of) the stepping stones towards solving them are very strange, seemingly unrelated to the task. As the Neuroevolution textbook puts it, these approaches “are motivated by the idea that reaching innovative solutions often requires navigating through a sequence of intermediate ‘stepping stones’—solutions that may not resemble the final goal and are typically not identifiable in advance”. For example, the worst way to become a billionaire is to get a normal corporate job and incrementally maximise your salary. A great example of a strange path to greatness was YouTube, which was started as a video dating website!

In our interviews with Stanley, he has repeatedly emphasised this point.

“The smart part is the exploration. The dumb part is the objective part because it’s freaking easy.

There’s nothing really insightful or interesting about just doing objective optimization. […] Once I say

that what you need to be good at is if I define where I want you to go and then you can get there, then

I’m basically training you not to be able to be smart if you don’t know where you’re going. But that’s

what creativity is. It’s about being able to get somewhere and be intelligent even though you don’t know

where your destination is.”

Prof. KENNETH STANLEY - Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned

Stanley therefore prescribes abandoning objectives, and becoming open-ended by searching for novelty.

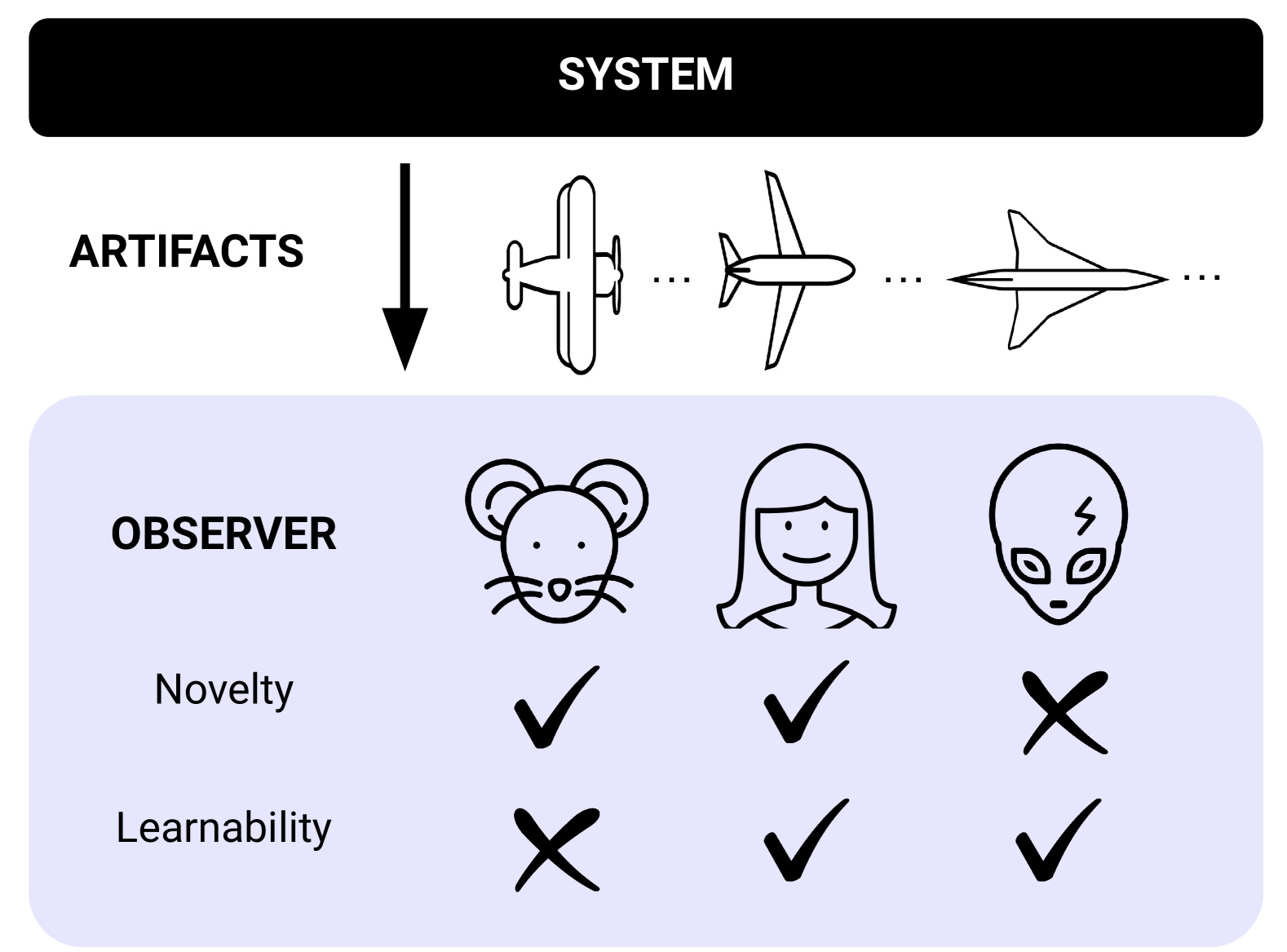

What exactly is open-endedness? In 2024, a team led by Tim Rocktäschel—the open-endedness team lead at Google DeepMind and Professor at UCL— formally defined an open-ended system as one which produces a sequence of artefacts which are:

- Novel, i.e. “artifacts become increasingly unpredictable with respect to the observer’s model at any fixed time”.

- Learnable, i.e. “conditioning on a longer history makes artifacts more predictable”.

We will return to this formal definition of open-endedness in Section 3, but for now notice what Chollet and Rocktäschel are both saying. Chollet’s general intelligence must “synthesize new programs” to “solve never-seen-before tasks”; Rocktäschel’s open-ended systems must produce “novel” and “learnable” artefacts. Both of these are describing creativity! The “standard definition of creativity” calls a work creative if it is (a) original or novel, and (b) effective or valuable. In our interview with Rocktäschel, Tim Scarfe observed: “I actually interpreted your definition of open-endedness as ... a definition of creativity”. Open-Ended AI: The Key to Superhuman Intelligence? Creativity is thus the key to efficient generalisation and to open-ended exploration.

Agency requires intelligence—you cannot have directed, purposeful behaviour without some capacity to model and respond to the world (Schlosser 2019). In biological systems, intelligence and agency co-evolved and remain tightly coupled. But artificial intelligence need not be agentic; there is no reason a system with knowledge and reasoning capacity must also have future-pointing control. Still, even when intelligence is coupled with agency, Stanley’s point still holds: fixed goals can constrain the very creativity needed to find problems worth solving—unless the agent happens to be pointing in the right direction already, as we will discuss later.

1.3 Is that all there is to AI creativity?

The “standard definition” lays out two criteria for creativity, but are those all you need? Creativity theorist Mark Runco thinks not. In two 2023 essays, Runco agreed that AI systems can, and indeed have, produced novel and effective outputs—but argued that we must not focus only on the products of a system and ignore the processes by which those are produced. Runco adds two more criteria: authenticity and intent.3

A system is authentic if it acts in accordance with beliefs, desires, motives etc. that are both its (rather than someone else’s) and express who it “really is”; authenticity is the opposite of being derivative. A system has intent if it is the reason why it does the things it does. If an AI system solves problems, but neither finds those problems nor has any intrinsic motivation to solve them, are those solutions really creative?

Both of Runco’s criteria speak to a key distinction: creative ideas are not just original (a property of the product) but must also originate (a process) from their creator. Runco argues that AI systems lack key processes of human creativity, such as intrinsic motivation, problem-finding, autonomy, and (most starkly) the expression of an experience of the world. Runco concludes:

“Given that artificial creativity lacks much of what is expressed in human creativity, and it uses wildly different processes, it is most accurate to view the ostensibly creative output of AI as a particular kind of pseudo-creativity.”

But is Runco right about the creativity needed for intelligent reasoning, rather than creative expression? Must this look like human creativity? To borrow a comment from Richard Feynman: our best machines don’t go fast along the ground the way that cheetahs do, nor fly like birds do. A jet aeroplane uses “wildly different processes” to fly than an albatross, but is it pseudo-flying? We are not claiming that different processes cannot work—only that the particular processes used by current AI systems demonstrably fail in ways (adversarial brittleness, lack of transfer, derivative outputs) that reveal shallow pattern-matching rather than genuine comprehension. The principled distinction is this: understanding constrains and guides the creative search—without it, outputs are derivative or random. Intent merely motivates the search. You can be creative by accident (Spencer’s microwave, evolution itself), but you cannot be creative without respecting constraints. That is why we require understanding but not intent.

Remember our central question: what qualities do AI systems need to perform reasoning tasks (planning, science, coding, etc.) in generalisable and robust ways? As we have seen, something that looks like, and quite possibly quacks like, creativity is needed. We must now ask: are authenticity and intent required for this creativity?

2 Creativity needs to respect the phylogeny

“I believe that it is possible, in principle, for a computer to be creative. But I also believe that being

creative entails being able to understand and judge what one has created. In this sense of creativity, no

existing computer can be said to be creative.”

— Melanie Mitchell, Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking Humans (Mitchell 2019)

2.1 Being inspired vs. being derivative

Can something derivative ever be creative? Is not a derivative system, in the end, merely laundering ideas from somewhere else? There is no creativity in the plagiarist. But one might object— as Alan Turing noted—with the old saw that “there is nothing new under the sun”. Is not all creation derivative? Do not all creatives, from Shakespeare to Newton, stand on the shoulders of giants?

To make sense of this, we must distinguish being inspired—where existing material flows through a creator, who makes it their own—from being derivative, where existing material is pieced together with little deliberate input from the creator. The quintessential derivative system is a photocopier, which copies with zero understanding. Mitchell was onto something: understanding is crucial for authentic human creativity.

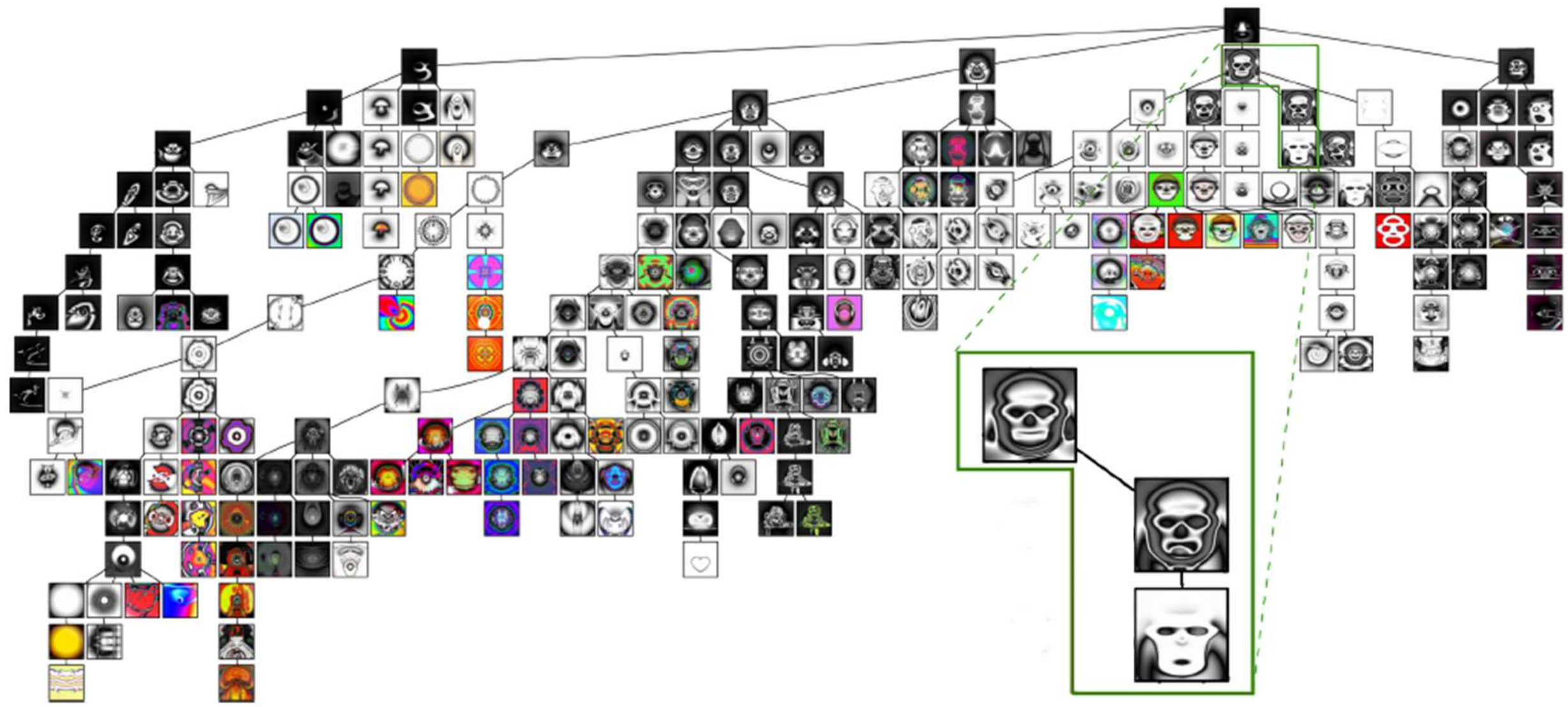

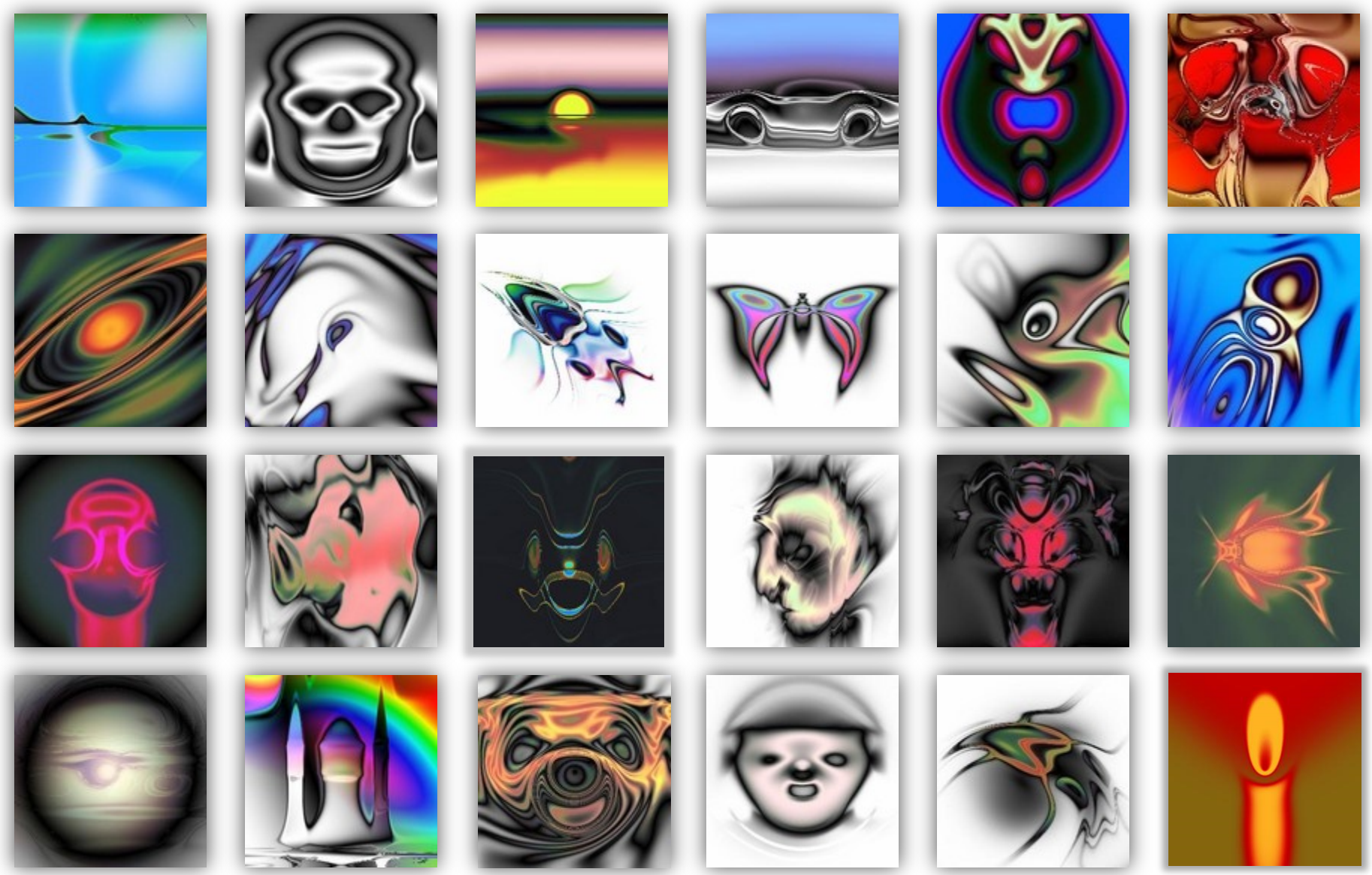

Understanding of what, exactly? We can draw a wonderful illustration by looking at Kenneth Stanley’s 2007 Picbreeder website experiment. On Picbreeder, users could start from an image, get that image to produce “children”, then chose which child would be their new image, and so on. Behind the scenes, these images were being produced by neural networks, which evolved in response to the user’s choice via Stanley’s NEAT algorithm (NeuroEvolution of Augmenting Topologies)—an evolutionary method that grows network structure incrementally. The project was collaborative: users could publish their images, and other users could start from published images rather than from scratch, creating a phylogeny of images.

In a 2025 paper, Akarsh Kumar and Kenneth Stanley point out that the networks producing these images have incredibly well-structured representations. Changing different parameters in the “skull” network could make the mouth open and close, or the eyes wink. In our interview with Stanley, he argued that the crucial ingredient was the open-ended process by which users arrived at these images:

“On the road to getting an image of a skull, they were not thinking about skulls. And so, like when they

discovered a symmetric object like an ancestor to the skull, they chose it even though it didn’t look like

a skull. But that caused symmetry to be locked into the representation. You know, from then on,

symmetry was a convention that was respected as they then searched through the space of symmetric

objects. And somehow this hierarchical locking in over time creates an unbelievably elegant hierarchy of

representation.”

Deep Learning has “fractured" representations [Kenneth Stanley / Akarsh Kumar]

These remarkable representations were the result of users respecting the phylogeny of the images they manipulated. By contrast, when Kumar et al. trained the same network to produce a Picbreeder image directly via stochastic gradient descent (SGD), ignoring this phylogeny, the image was almost identical but the representations were “fractured and entangled”—in a word, garbage. Where the evolved network had parameters mapping to meaningful features—symmetry, mouth shape, eyes—the SGD-trained network smeared these across its weights with no interpretable structure. As Stanley put it: the SGD skull is “an impostor underneath the hood”. The Neuroevolution textbook generalises this finding:

“Where SGD tends to entrench fractured and entangled representations, especially when optimizing toward a single objective, NEAT offers a contrasting developmental dynamic. By starting with minimal structures and expanding incrementally, NEAT encourages the emergence of modular, reusable, and semantically aligned representations.”

All ideas have a phylogeny in this way—most much subtler and more complex than in Picbreeder—and respect for this phylogeny is the difference between inspiration vs. being derivative. Inspiration is about understanding the phylogenies of the ideas one borrows, and thereby creating new works that deliberately extend those lineages. Ironically, to be “derivative” is to derive too little from one’s sources!

Among the riches of the phylogeny are what Daniel Dennett called “free-floating rationales”: reasons for a design’s structure that exist whether or not any mind grasps them. The eye has reasons for having a lens, but nobody had to understand them for the lens to evolve. In human creativity, by contrast, those same rationales become represented, manipulable, transferable.

This understanding comes in different levels. At the lowest is shallow, surface-level understanding, drawing very little from the riches of the phylogeny. A forger may paint a perfect copy of the Mona Lisa yet be hopeless at painting a new portrait, because all they understood was paint on canvas. Systems like Midjourney may produce impressive images, but their outputs are derivative of their vast training data (and users’ prompts) sometimes to the level of, in Marcus and Southern’s words, “visual plagiarism”. These systems consume billions of images, but only as collections of pixels, and often demonstrate basic misunderstandings of image content, such as struggling to draw watches at times other than 10:10. This shallow understanding leads only to a “creativity” that recombines and remixes existing ideas. In her essay “What is creativity?”, Boden called this “combinational creativity”, but because these systems recombine without understanding—without grasping why the pieces fit—we prefer to call it, at best, quasi-creativity. It may produce novel outputs, but there are no new ideas underlying those outputs—just existing ones arranged in a new way.

The next level is domain-specific understanding. By understanding how the ideas and tools work within a domain (or what Boden calls a “conceptual space”) one obtains “exploratory creativity”, the ability to discover new possibilities within that space. This is the workhorse of human creativity. As Boden urges, “many creative achievements involve exploration, and perhaps tweaking, of a conceptual space, rather than radical transformation of it”—Nobel Prizes reward “ingenious and imaginative problem solving”, not Kuhnian revolutions. Even some of our most celebrated creative achievements stem from thinking deeply “inside the box”.

Finally, the highest level is domain-general understanding. When one understands one’s tools in themselves, beyond their common or intended uses, one can use them in ever more creative ways. A wonderful example of this in action is the “square peg in a round hole” scene from Apollo 13. Domain-general understanding is the key to what Boden calls “transformational creativity”, the ability to create new conceptual spaces. To make sense of a new conceptual space, one must understand how to extend phylogenies into this new domain—to understand gravity but not as a force, or harmony but without a tonal centre. To think “outside the box”, one needs to understand what happens to one’s tools when they are taken out of the box.

The boundary between exploration and transformation lies, somewhat, in the eye of the beholder. One person’s “new domain” might be another’s “new possibility within a domain”. Therefore, the key question is not “can we make transformatively creative AIs?” Stanley remarked on a draft of this very article that he thinks of combinatorial and exploratory creativity as ways to find a new location within the space you’re in, whilst transformational creativity is about “adding new dimensions to the universe”. In this view, NEAT’s complexification operators—which add new nodes and connections to an evolving network—are a concrete realisation of transformational creativity. Boden argued that a prima facie transformatively creative AI was built as far back as 1991 by Karl Sims. Instead, we should ask how deep the AI’s understanding was that led to its surprising outputs, and what spaces it can and can’t make sense of.

A derivative system (ironically: not derivative enough!) will not generalise—it lacks the phylogenetic understanding needed to extend ideas into unfamiliar settings, and its reliance on surface features makes it brittle.

All this said, derivative systems may still be useful for reasoning: they might extract ideas or reasoning patterns which, whilst pre-existing in data (or the user!), were previously inaccessible. This may be very valuable in creative reasoning pipelines—as we will soon explore. Not all AI systems are equally derivative. Google DeepMind’s AlphaZero had, well, zero training data, and we will later explore the extent of AlphaZero’s creativity.

2.2 Agency, intent, and Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned

What about Runco’s criterion of “intent”? This, alongside the stronger sense of authenticity as expressing “who one really is”, suggests that agency is needed for creativity. By agency we mean control over the expected future—taking actions now to shape what comes next. As Claude Shannon, the founder of information theory, observed: “We know the past but cannot control it. We control the future but cannot know it.”4 Agency operates in this gap: we act on our expectations, which may prove wrong, and we can acquire new goals as understanding evolves. Surely the more agency you have, the more creative you can be, right?

Only the plot thickens, since as Stanley says, greatness cannot be planned! Too much agency—too much control—is anathema to creativity. Stanley’s insight is that the most fertile ground for creativity is when you are unfettered and serendipitous. Serendipity doesn’t imply greatness, but it’s so often present when greatness occurs!

But we must be careful here. The point is not that you should have no agency at all—quite the opposite. Follow someone else’s objectives and you explore their search space, not your own; surrendering your agency is, on average, the worst way to be creative, because you are less likely to stumble upon spaces that only your particular trajectory could reach. The real insight is about the kind of agency that matters: agency diffused across many independent actors, each following their own gradient of interest.

Both creativity and intelligence use priors—the difference is direction. Intelligence converges toward a known goal; creativity diverges into unknown territory, using constraints to keep the search coherent. Constraints enable rather than determine: grammar constrains what you can say without determining it; physics made eyes possible without encoding them as a destination. Evolution has no agency— it cannot plan—but exhibits teleonomy: apparent goal-directedness from selection pressure rather than intention (Pittendrigh 1958). For agents who can plan, a different kind of agency helps creativity: the “nose for the interesting” that Stanley emphasises—taste-driven, intuitive orientation toward the unknown. As Stanley puts it:

“The gradient of interestingness is probably the best expression of the ideal divergent search.

Not everything that’s novel is interesting, but just about everything that’s interesting is

novel.”

Prof. KENNETH STANLEY - Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned

The best ideas are often those you were not seeking. One day in 1945, the engineer Percy Spencer was working on a radar set, and when he stood near a cavity magnetron, the chocolate bar in his pocket melted! Spencer recognised this sticky misfortune for what it truly was: it was an unplanned experiment on what microwaves do to food, and he understood what it meant— leading him to invent the microwave oven! Creativity is thus less about one’s control over the world, and more about one’s ability to adapt to the curveballs the world throws, grounded in one’s deep understanding.

Intent is, therefore, not a necessary condition for creativity. Both purposeful and non-purposeful creativity can work; human creativity often involves unintended twists, and as we’ve seen, creativity doesn’t require agency at all. It may not matter if an AI theorem prover does not care about the Riemann Hypothesis, or if a driverless car does not choose its destination. But a creative output must originate in a system for us to call that system creative for producing it, and this origination requires being grounded in and deliberately extending the phylogeny.

Can anything originate in an AI system? Ada Lovelace, the first ever computer programmer, famously argued that it couldn’t:

“The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform.”

Boden gives a key response to Lovelace: what if an AI system changes its own programming? We can order it to perform some task, but allow it to determine how exactly it does so. Boden points to evolutionary algorithms, such as in Bird and Layzell’s 2002 “Evolved Radio”, as permitting AI systems to give themselves genuinely novel (to the AI) capabilities.

Doing things one wasn’t ordered to do is not enough, though. As Mitchell argues, creativity requires understanding and judging what one has created (Mitchell 2019). A monkey at a typewriter might produce Hamlet, but it could never repeat this miracle—origination requires a process that systematically produces that sort of thing. Spencer’s chocolate melting was an accident, but it was no accident that it led him to invent the microwave oven; had the bar melted some other day, he would have invented it just the same.

So we have a framework: creativity requires respecting the phylogeny, and origination requires understanding. How do today’s AI systems measure up?

3 Are LLMs creative?

The test is whether these systems respect the phylogeny, and whether what they produce can be said to originate in them. We start with LLMs—trained on vast quantities of human text—then turn to game-playing systems like AlphaGo and AlphaZero, which learn from self-play alone. Each fails differently, and the contrast sharpens the picture.

Way back in 2019—when, as far as LLM history is concerned, dinosaurs roamed the Earth—the lowly GPT-2 could write poems.

Fair is the Lake, and bright the wood,

With many a flower-full glamour hung:

Fair are the banks; and soft the flood

With golden laughter of our tongue

Not bad for such an antiquated model, right? Well, not exactly. This poem is a short extract from a list of a thousand samples, 99.999% of which is junk. One finds many patterns in clouds, but the clouds are not creative!

ChatGPT was something new. Suddenly, here was a system you could ask to write an email as a Shakespearean sonnet, and it just... would. It wouldn’t be perfect, or even all that good, but you wouldn’t have to sift through pages of nonsense. And then GPT-4 landed a few months later, and was so much better. The hype went into overdrive; the exponential was upon us. No wonder that within weeks of GPT-4’s release, there were predictions of “ AGI within 18 months”!

But now the hype has started to fade. The systems are more capable than ever, yet people are increasingly unimpressed. GPT-5 landed less with a bang and more with a shrug.5 What is going on? Are these systems showing any creativity, or even quasi-creativity? Are they wholly uncreative “ stochastic parrots”? Why have LLMs lost their shine?

3.1 Can you measure LLM creativity?

Measuring creative thinking is not straightforward. One of the “ 6 P’s of Creativity” is persuasion: a truly creative reasoner can produce “wrong” solutions just as valid as the “right” answer, and a benchmark that cannot be persuaded will reject them— this has already happened. Still, some aspects can be tested. In a 2024 Nature study, GPT-4 outperformed humans on three standard divergent thinking tasks—generating unusual uses, surprising consequences, and maximally different concepts. As computer scientist Subbarao Kambhampati emphasised:

“We think idea generation is the more important thing. LLMs are actually good for the idea

generation [...] Mostly because ideas require knowledge. It’s like ideation requires shallow

knowledge and shallow knowledge of a very wide scope. [...] Compared to you and me, they

have been trained on a lot more data that even if they’re doing shallow, almost pattern

match across their vast knowledge, to you it looks very impressive. And it’s a very useful

ability.”

Do you think that ChatGPT can reason?

(Note Kambhampati’s careful phrasing: “shallow” and “almost pattern match”. LLMs often act as if they have knowledge, but they cannot distinguish truth from statistical association—they lack the grounding that would make it knowledge proper.)

But divergent thinking is only half of creativity. Who cares if GPT-4 can list more uses of a fork than you can, if none of those uses are any good? The Allen Institute’s MacGyver benchmark (Tian et al. 2024) tests creative problem solving—e.g., heating leftover pizza in a hotel room using only an iron, foil sheets, a hairdryer, and similar everyday items. Humans outperformed all seven LLMs tested (including GPT-4), though GPT-4 came close.

3.2 LLMs, N-gram models, and stochastic parrots

Kambhampati has provocatively called LLMs just “ N-gram models on steroids”. N-gram models—the “ quintessential stochastic parrot” (DeepMind’s Timothy Nguyen)—predict the next token by pattern-matching against the previous N-1 tokens. In a 2024 NeurIPS paper, Nguyen found that LLM next-token predictions agreed with simple N-gram rules 78% of the time (160M model on TinyStories) and 68% (1.4B model on Wikipedia). Are LLMs creative at all?

But Nguyen carefully states his finding: he found that 78% of the time, the LLM’s next-token-prediction could be described by the application of one or more N-gram rules, from a bank of just under 400 rules. This does not explain the LLM’s prediction: it does not say how or why that particular rule was selected. In our interview with Nguyen, he noted how Transformers cannot be a static N-gram model if they are to adapt to novel contexts:

“Famously one of the weaknesses of N-gram models is what do you do when you feed it a context it

hasn’t seen before? [...] The reason I have all these templates is in order to do robust prediction; the

Transformer has to do some kind of negotiation between these different templates, because you can’t get

any one static template, that will just break.”

Is ChatGPT an N-gram model on steroids?

A human writer constrained to match N-gram predictions 80% of the time could still write creative stories—being describable by simple rules does not make one a parrot. But that does not mean LLMs are creative for the same reason. What they are doing comes from compression. As Kambhampati notes, the number of possible N-grams grows exponentially in N, and once you get to the context size of even “the lowly GPT-3.5”, let alone recent LLMs, the number of N-grams is essentially infinite, dwarfing the parameter count of any LLM.

“So because there’s this huge compression going on, interestingly, any compression corresponds to some

generalization because, you know, you compress so some number of rows for which there would be zeros

before now there might be non-zeros.”

Do you think that ChatGPT can reason?

This generalisation corresponds to combinational quasi-creativity: the LLM will perform this compression by interpolating the N-grams in its training data.

3.3 LLM “creativity” is highly derivative

This interpolation, however, does not give a deeper, genuine creativity. As Kambhampati says, LLMs are doing a shallow pattern-match over vast data. Every idea in that data has a phylogeny—a structured lineage of prior discoveries it builds on. LLMs consume the products of these lineages but not the lineages themselves, and by neglecting this phylogeny they fail to exhibit genuine creativity—they do not understand beyond a surface-level. This is why LLMs have lost their shine: at first, their surprising combinations were impressive. But as they made more and more stuff, their blandness and shallowness became more and more evident, even as their technical quality improved.

Recall Rocktäschel’s formal definition of open-endedness: a system is open-ended when its artefacts are both novel and learnable from the observer’s perspective.

In Rocktäschel’s terms, LLM outputs may be learnable but lack genuine novelty—they produce new artefacts without producing surprising ones. As Stanley puts it:

“It can do some level of creativity, what I would call derivative creativity, which is sort of like the bedtime story version of creativity. It’s like you ask for a bedtime story, you get a new one. It’s actually new. No one’s ever told that story before, but it’s not particularly notable. It’s not gonna win a literary prize. It’s not inventing a new genre of literature. Like, there’s basically nothing new really going on other than that there’s a new story.”

Do these combinations originate in the LLMs? One might suspect they merely “render” ideas already in their prompts, but random-prompt experiments refute this—generative models produce coherent, surprising images from pure gibberish:

Prompt: }?@%#{.;}{/$!?;,_:-%$/+$*=}+={ into DALL-E 3

These outputs plainly depend on training data, not prompts. That said, the more you prompt engineer an LLM, the more the “renderer” analogy applies: the creations originate more in you.

The novelty of LLM outputs is in a sense accidental: the global minimiser of the training objectives of generative AI models perfectly memorise their training data (Bonnaire et al. 2025). These systems produce novel outputs only because they aim at that target and miss; they compress an entirely plagiarising model into something their parameters can express, and thus produce novelty by accident of training. If you tried to write out The Lord of the Rings from memory, and of course failed, you would technically have written a novel book, but trying to plagiarise and failing ( and not always failing!) is a very shallow form of “creativity”. Just like the SGD-trained Picbreeder networks, the selectional history of LLMs—the history of what their training process rewarded—favours the wrong abilities.

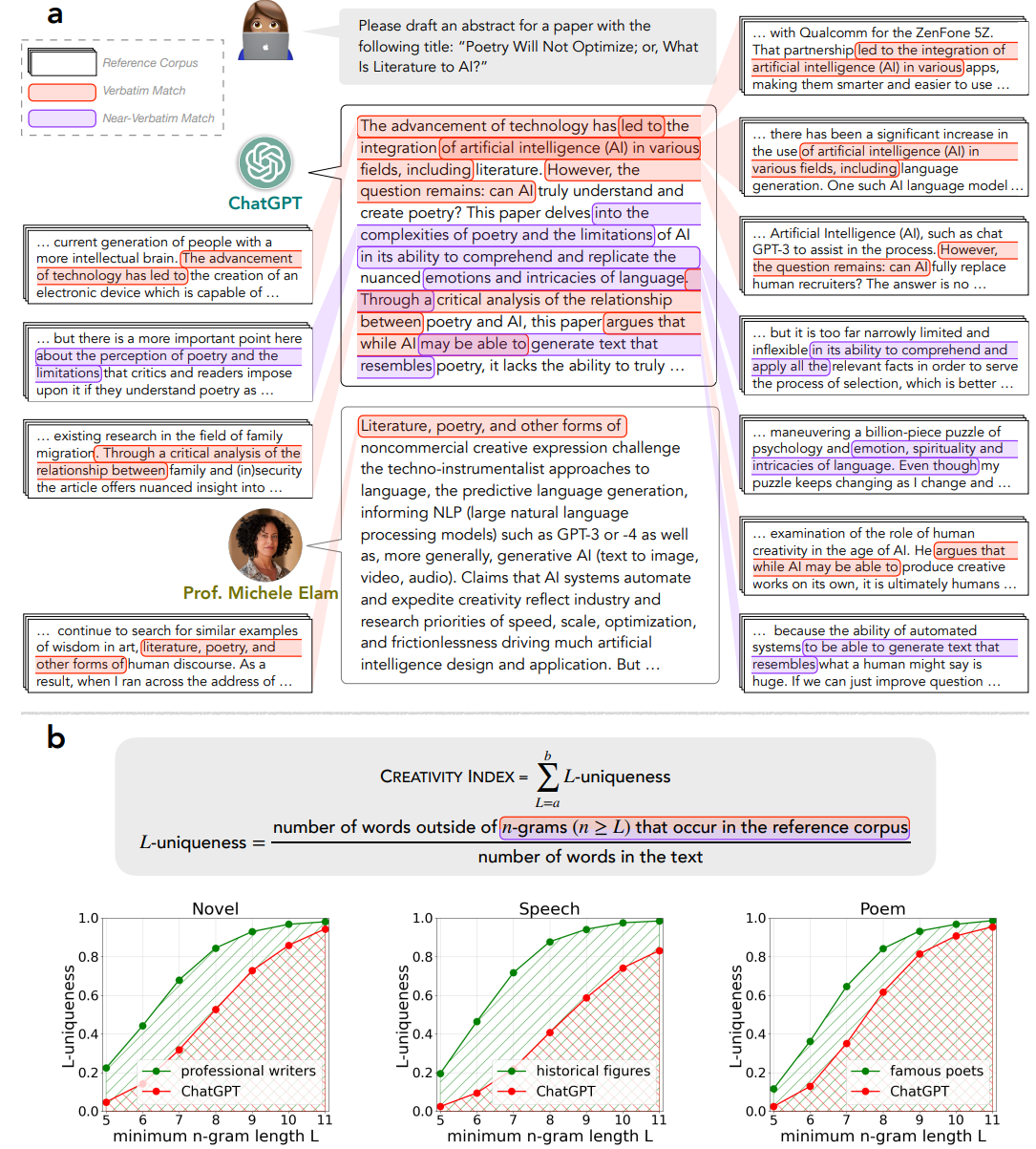

Using the Allen Institute’s Creativity Index, we can even measure how derivative LLMs are. Introduced in a 2025 study, the Creativity Index quantifies the “linguistic creativity” of a piece of text by how easily one can reconstruct that text by mixing and matching snippets (i.e., N-grams) from some large corpus of text.

Comparing writings by professional writers and historical figures to LLMs (including ChatGPT, GPT-4, and LLaMA 2 Chat), the study found that human-created texts consistently had significantly better Creativity Index than LLM-generated texts, across various types of writing. Curiously, it also found that RLHF (reinforcement learning from human feedback) alignment significantly worsened Creativity Index. This provides empirical evidence that the originality displayed by LLMs is ultimately combinational—by actually finding what might have been combined!

3.4 What about Large Reasoning Models?

But what about creative reasoning? Pure LLMs like GPT-4 struggled at reasoning. On Chollet’s Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus (ARC-AGI) benchmark, GPT-4.5 managed just 10.3% on ARC-AGI-1 and 0.8% on ARC-AGI-2! It was pretty easy to come up with mathematics questions that would stump these LLMs. And Kambhampati demonstrated that GPT-4’s performance on a planning benchmark could be utterly ruined by “obfuscating” the tasks in ways that preserved their underlying logic. Had GPT-4 been using a reasoning process, it would have been robust to this obfuscation; its failure demonstrated that it was not solving any of the tasks by reasoning.

But on December 20, 2024, OpenAI’s o3 model landed with a bang, announcing 87.5% on ARC-AGI-1. o3 was still an LLM at its core, but one fine-tuned via reinforcement learning to “think” at inference time, producing an internal “chain-of-thought” which it used to produce its answer. The coming weeks saw the release of OpenAI’s o3-mini, DeepSeek’s R1, and Google’s Gemini Flash Thinking, and the age of the large reasoning model (LRM) was begun. Did these change the game? Can LRMs reason creatively?

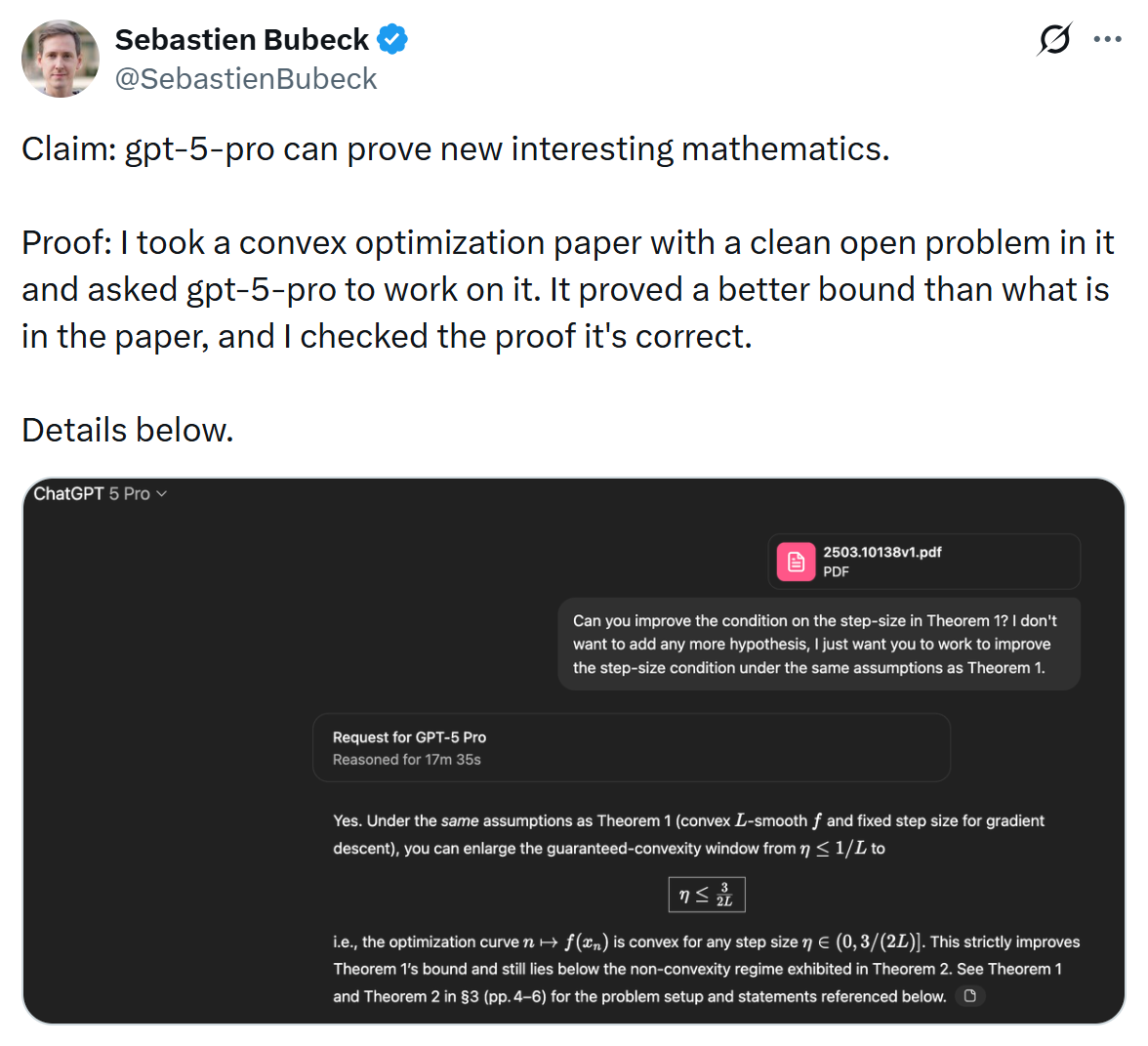

Their progress in mathematics has certainly been dramatic, with both Google DeepMind and OpenAI announcing gold in the 2025 International Mathematics Olympiad (IMO). OpenAI researcher and mathematician Sébastien Bubeck claimed in an August 2025 tweet that GPT-5-pro could prove “new interesting mathematics” by improving a theorem in a provided convex optimisation paper. And on ARC, LRMs crowd the leaderboard, with Opus 4.6, GPT 5.2, and Gemini 3 all over 50% on ARC-AGI-2.

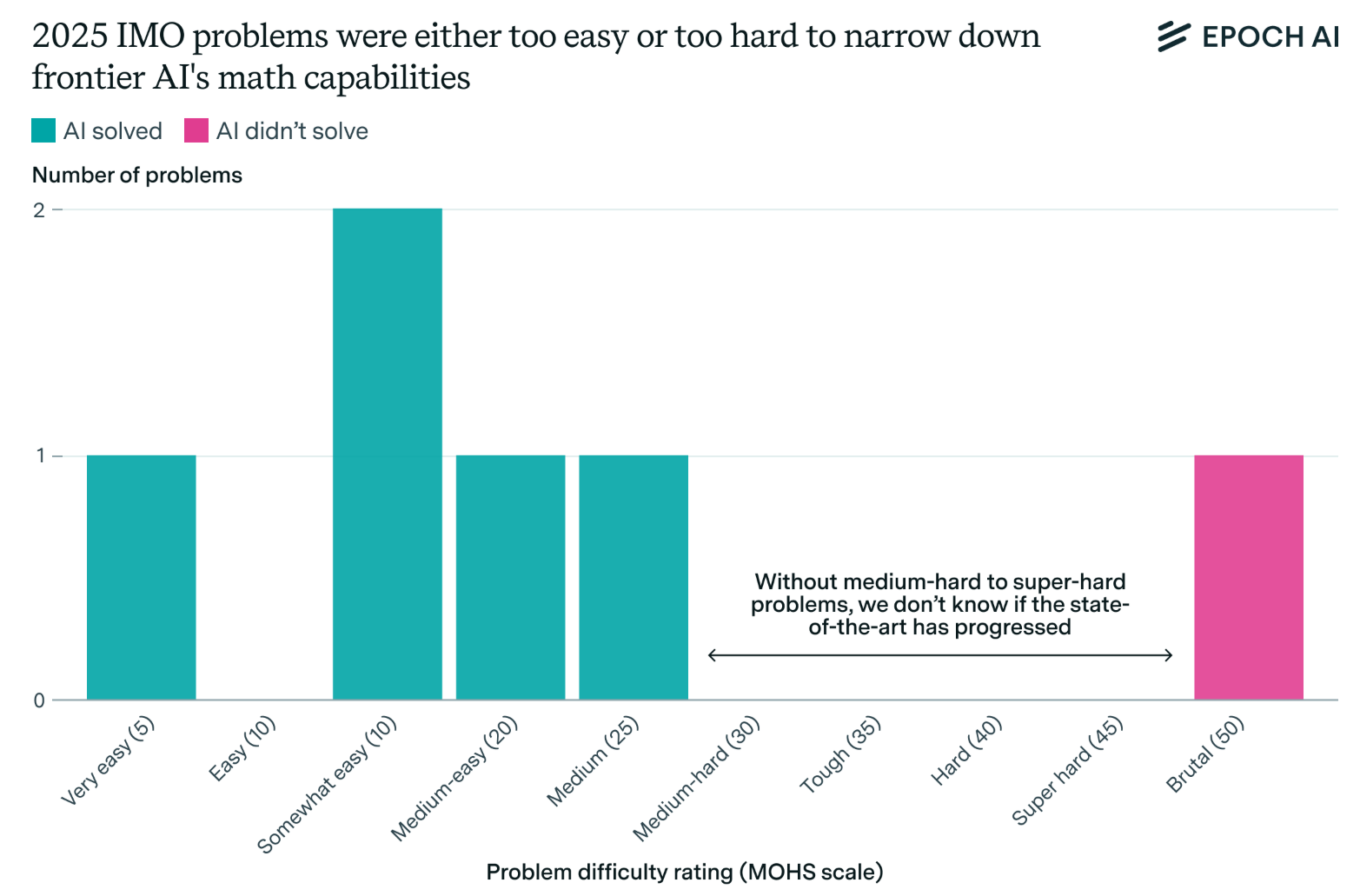

However, these performances may be misleading. Greg Burnham at Epoch AI argues that the 2025 IMO was unfortunately lopsided, with the five questions that the LRMs could solve being comparatively easy (as judged by the USA IMO coach), and the one they couldn’t solve being brutally hard.

For our topic, the only question Burnham judges as requiring “creativity and abstraction” was the one the LRMs couldn’t do! The others, though far from simple, could be solved formulaically. Bubeck’s example follows a similar pattern: although the improvement would indeed have been novel (had a version 2 of the paper with an even better improvement not already been uploaded), GPT-5’s proof is a very standard application of convex analysis tricks; tricks it had already seen in the original paper. GPT-5 uses these tricks well, but not especially creatively. To co-author (and mathematician) Jeremy’s eye, the v2 paper proves a better result and has a more creative proof. Perhaps these LRMs are simply teaching mathematicians the lesson Go world champion Lee Sedol learned from AlphaGo:

“What surprised me the most was that AlphaGo showed us that moves humans may have thought are

creative, were actually conventional.”

— Lee Sedol, AlphaGo - The Movie

Except, unlike AlphaGo, so far in mathematics LRMs have “ told us nothing profound we didn’t know already”, to quote mathematician Kevin Buzzard.

On ARC, an October 2025 paper by Beger, Mitchell, and colleagues (Beger et al. 2025) explored whether LRMs grasp the abstractions behind ARC puzzles. Using the ConceptARC benchmark, whose ARC-like puzzles follow very simple abstract rules, Mitchell tasked o3, o4-mini, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and Claude Sonnet 4 to solve the puzzles and explain (in words) the rules which solve them. Mitchell found that although the LRMs scored as high as 77.7% on the tasks, beating the human accuracy of 73%, compared to humans a lot more of the LRMs’ correct answers relied on rules which did not correspond to the correct abstraction. This suggests that the LRMs were still reliant on superficial patterns, and did not fully understand the puzzle. However, it is possible this analysis could change with SOTA models like Opus 4.6, GPT 5.2, and Gemini 3.

When it comes to creativity, LRMs have the same core issues as LLMs. An LRM is an LLM which has been fine-tuned to produce—instead of simply the most probable next token—a “chain-of-thought” which resembles those it saw in training data. Done well, this enables the LRM to indeed produce, for example, very clean mathematical proofs, when those use standard techniques or patterns. But when presented with a novel problem, this generated chain-of-thought must not be mistaken for the model understanding that problem, and deliberately taking steps to solve it. Kambhampati warns against anthropomorphising (Kambhampati, Valmeekam, Gundawar, et al. 2025) these so-called “reasoning tokens”, arguing that these mimic only the syntax of reasoning, and lack semantics. The chain-of-thoughts parrot the way humans write about thinking, but may not reflect the actual way the LRMs produce their answers. Even fine-tuning an LRM on incorrect or truncated reasoning traces has been found to improve performance vs. the base LLM (Li et al. 2025), suggesting that performance gains do not derive from the LRM learning to reason, but merely from learning to pantomime reasoning. LRMs technically synthesise new programs on-the-fly, but very inefficiently and shallowly.

3.5 LLM-Modulo: LLMs as an engine for creative reasoning

So, is that it? Are LLMs and LRMs a nothingburger when it comes to intelligent, creative reasoning? Well, let us not be too hasty. As we have argued, these systems fail because they lack deep understanding, lack semantics, lack grounding in the phylogeny. But what if you hooked an LLM up to something which did?

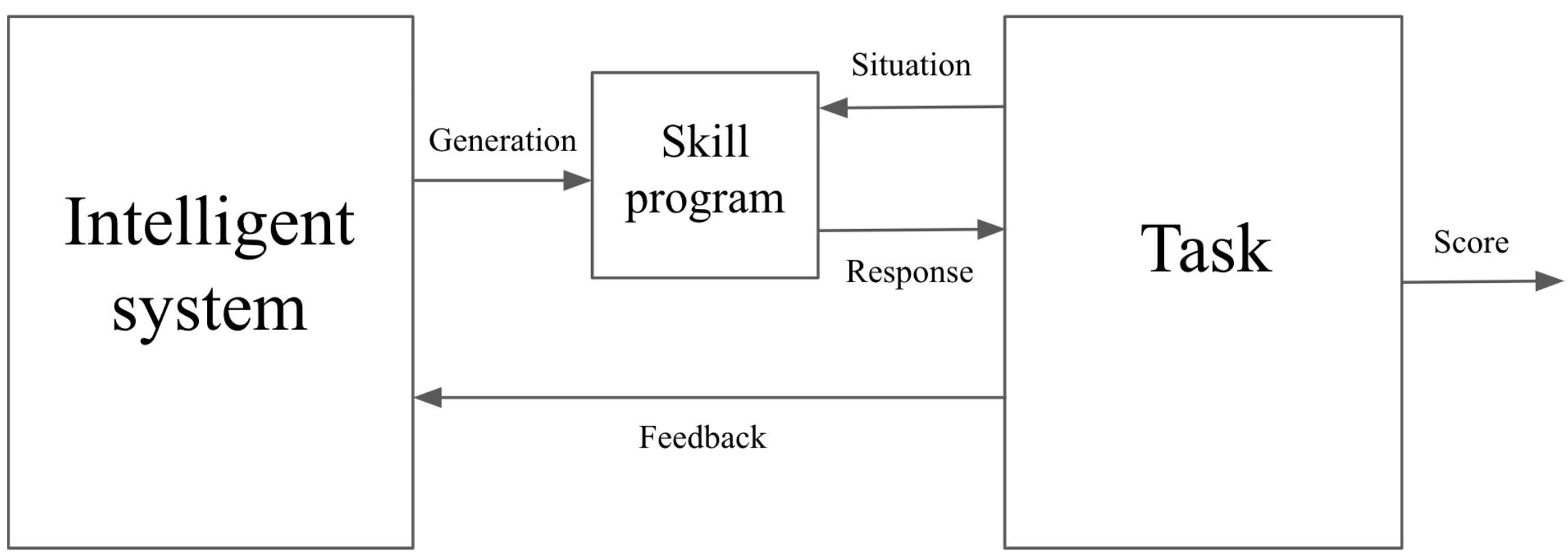

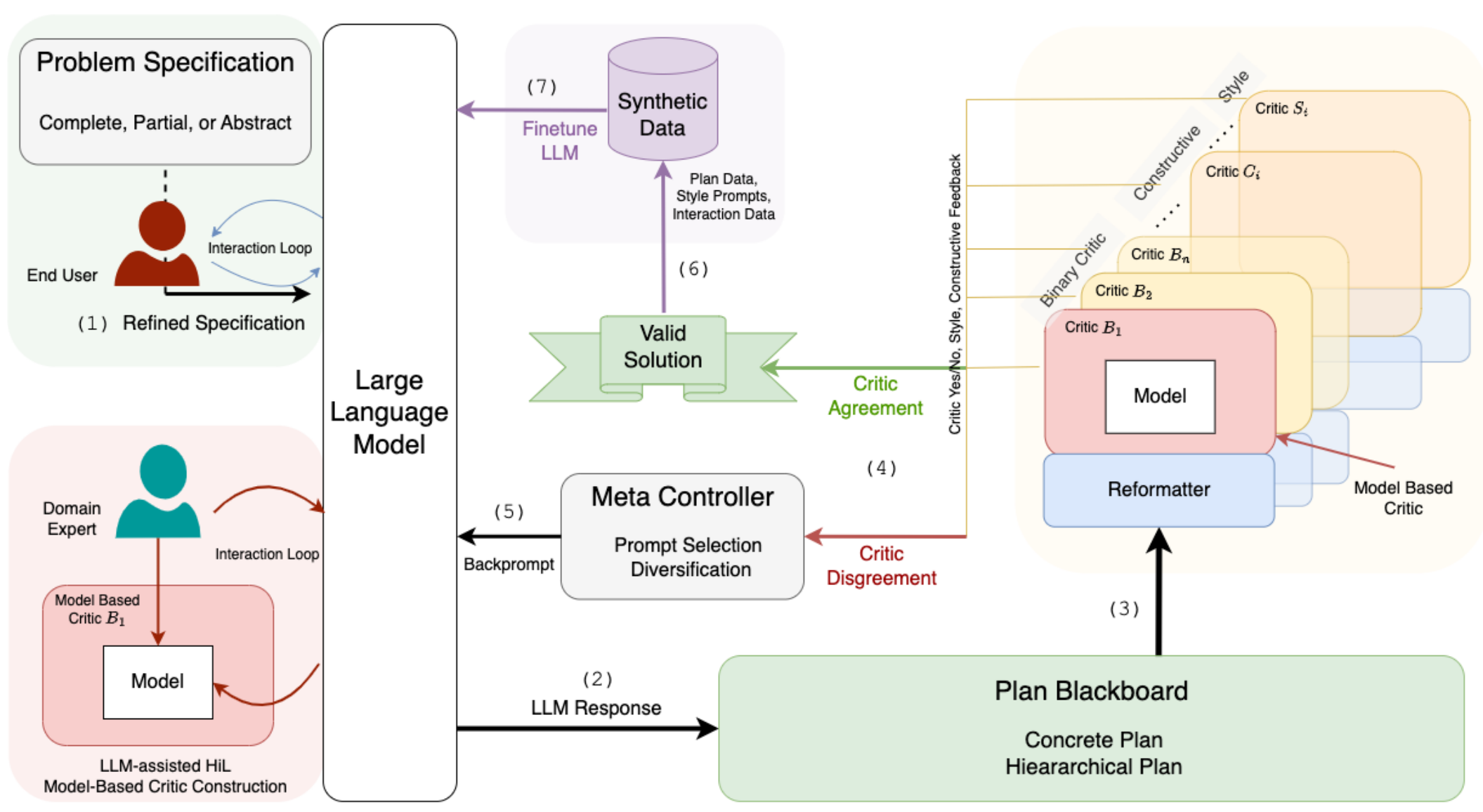

This is the key idea of Kambhampati’s LLM-Modulo framework. In LLM-Modulo, an LLM (or LRM) is an engine which generates plans to solve some task, but these plans are then fed into external critics which evaluate their quality. These critiques then backprompt the LLM to produce better plans, until the critics are satisfied. This generate-and-test pattern echoes psychologist and philosopher Donald Campbell’s “blind variation and selective retention” theory (Campbell 1960): knowledge and creative thought, biological or otherwise, require generating candidates without foresight and then selecting those with quality.

These critics can ground the system. Even if to an LLM the plans are just syntax, the critics, which potentially have rich representations of the task, can thereby imbue the LLM outputs with semantics. Do critics make the LLM more or less creative? The answer is nuanced: they bind the LLM to their specific domain, but this unlocks creativity within that domain. As we will later explore, constraints, not freedom, are the soul of creativity.

On ARC, this pattern has proved decisive. Ryan Greenblatt achieved 50% on ARC-AGI-1 by having GPT-4o generate Python programs and checking them against training examples—the Python interpreter as critic. Jeremy Berman took SOTA on ARC-AGI-2 with a variant using English instructions and LLM-based checking.

Most recently, Johan Land reached 72.9% on ARC-AGI-2 by ensembling multiple LLMs with both Python and LLM-based critics. LLM-Modulo consistently gets LLMs to solve ARC puzzles far more accurately and efficiently than LLMs alone.

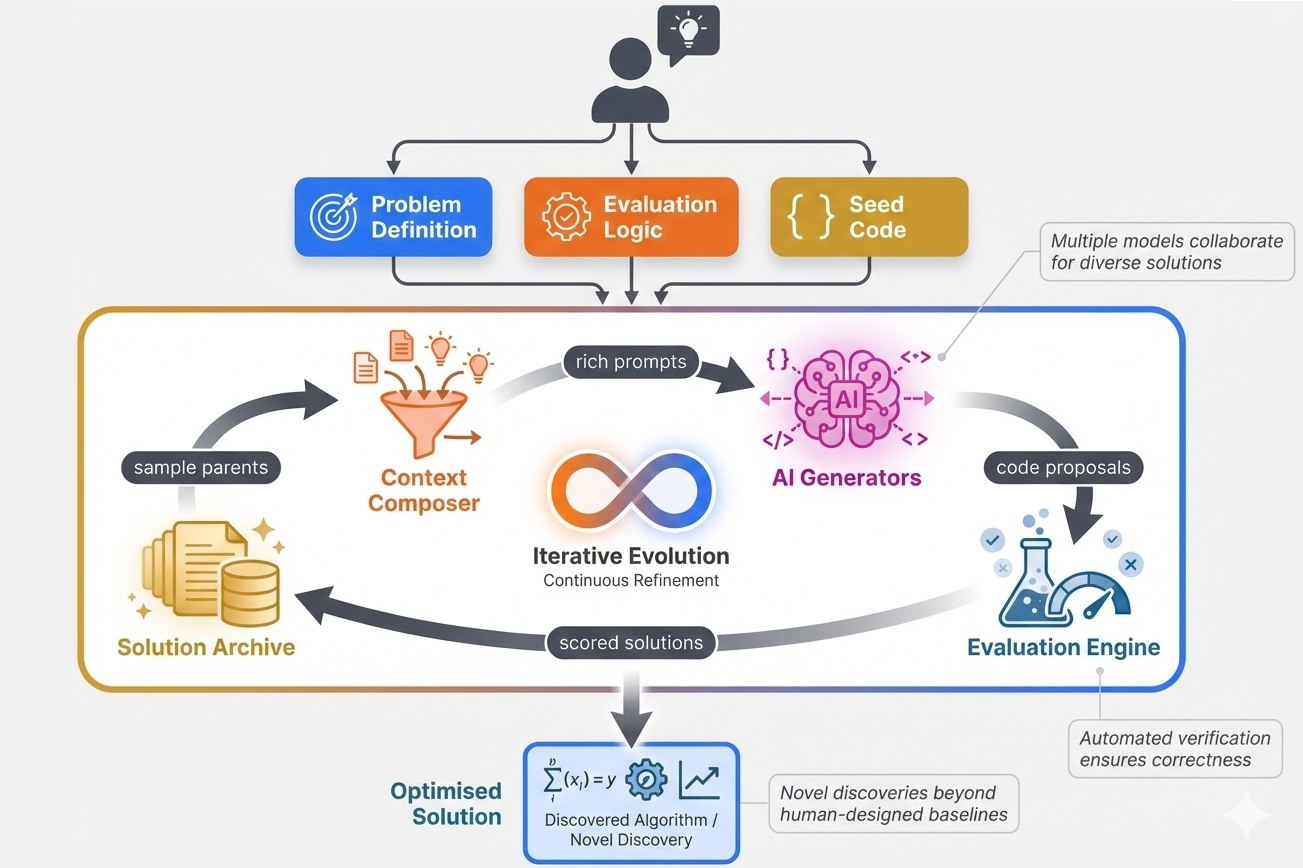

Beyond ARC, Google DeepMind’s AlphaEvolve (building on FunSearch (Romera-Paredes et al. 2024)) applies the same pattern: an ensemble of LLMs iteratively generates and improves programs, evaluated by external critics, with an evolutionary algorithm selecting the best candidates.

AlphaEvolve’s crown jewel: a novel method for multiplying 4x4 matrices in 48 multiplications, beating the 49-multiplication record held by Strassen’s algorithm since 1969.

So if, as Buzzard said, LRMs have “ told us nothing [mathematically] profound we didn’t know already”, LLM-Modulo systems like AlphaEvolve definitely have. LLM-Modulo allows these systems to be much more grounded in the phylogeny of their task, and evolutionary refinement means that these systems extend that phylogeny further. It is no coincidence that it is these systems which have produced more creative results than scaling LLMs and LRMs.

Nevertheless, these systems still rely on substantial engineering, and have so far only achieved success for narrow, well-defined tasks. To think about what that means for their creativity, let us leave LLMs behind us, and look at AlphaEvolve’s older siblings...

4 Are AlphaGo and AlphaZero creative?

In March 2016, DeepMind made headlines when its AlphaGo model defeated Lee Sedol, one of the strongest players in the history of Go. Go had long been a major challenge for AI systems due to its vast depth, and until AlphaGo no AI system had ever beaten a professional player. But AlphaGo was remarkable not only in its strength, but also in the originality of some of its moves. Particularly, AlphaGo’s move 37 in Game 2 amazed commentators, with Lee Sedol commenting:

“I thought AlphaGo was based on probability calculation and that it was merely a machine. But when I

saw this move, I changed my mind. Surely AlphaGo is creative. This move was really creative and

beautiful.”

— Lee Sedol, AlphaGo - The Movie

AlphaGo used data from human Go games to guide its play. But its even stronger successor AlphaGo Zero used no human data at all, learning only from the rules of Go. In December 2017, DeepMind went a step further and announced AlphaZero, a more general algorithm which could learn to play many games (e.g., Go, chess, and shogi) again just from self-play, with no human data. How was this done?

4.1 Monte Carlo Tree Search

At the heart of AlphaGo, AlphaGo Zero, and AlphaZero is Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS): from any position, the possible futures form a vast branching tree, and MCTS seeks the best path by sampling many branches in a guided way. AlphaZero’s MCTS was guided by a neural network that provided “intuitive” estimates of move quality and win probability. The key training loop iteratively amplified this intuition via MCTS reasoning, then distilled the conclusions back into an enhanced intuition. Through self-play, AlphaZero climbed from random play to superhuman performance. MCTS reasoning is vital: switch it off, and the raw model plays far worse.

4.2 The creativity of AlphaGo and AlphaZero

Are AlphaGo or AlphaZero really creative, or is this an illusion? According to Rocktäschel’s framework, AlphaGo is indeed open-ended:

“After sufficient training, AlphaGo produces policies which are novel to human expert players [...] Furthermore, humans can improve their win rate against AlphaGo by learning from AlphaGo’s behavior (Shin et al., 2023). Yet, AlphaGo keeps discovering new policies that can beat even a human who has learned from previous AlphaGo artifacts. Thus, so far as a human is concerned, AlphaGo is both novel and learnable.”

The same is true of AlphaZero—in chess, AlphaZero pioneered new strategies, famously loving to push pawns on the side of the board. AlphaGo Zero and AlphaZero cannot be recombining existing ideas—they aren’t given any! Unlike LLMs, who generalise somewhat by accident as a consequence of compressing their vast training data, AlphaZero plays positions it has never seen before by deliberately reasoning about them, via MCTS, and this ability was actively selected for by its training. But is this strong reasoning or weak reasoning?

There are key limits to AlphaGo/AlphaZero’s reasoning. As philosopher Marta Halina argues (Halina 2021), the limit of AlphaGo’s world is the standard game of Go; it is unable to play even mild variants of Go without retraining. Even AlphaZero, which can learn any two-player perfect-information game from its rules, can’t be trained on one game and then transfer that knowledge to other games. Therefore, Halina argues that:

“Computer programmes like AlphaGo are not creative in the sense of having the capacity to solve novel problems through a domain-general understanding of the world. They cannot learn about the properties and affordances of objects in one domain and proceed to abstract away from the contingencies and idiosyncrasies of that domain in order to solve problems in a new context.”

Rocktäschel concurs, calling AlphaGo a “narrow superhuman intelligence”. Why can’t it abstract away from Go’s contingencies? The answer lies in how it learns. Self-play with a fixed objective—win the game—is still greedy optimisation. Gradient descent tends to take the direct path to the goal, without pausing to discover foundational regularities first. As the fractured entangled representations paper argues—the same phenomenon we saw in Picbreeder’s SGD-trained networks—this creates representations like spaghetti code: redundant, entangled, with the same logic copy-pasted rather than factored into reusable modules. AlphaGo’s implicit grasp of “territorial influence” isn’t a separable concept it could apply elsewhere—it’s smeared across millions of weights, entangled with everything else it knows about Go. This is what we call concrete constraint adherence: the constraints are instantiated in AlphaGo’s substrate and shape its play, but they are not represented in a format it can manipulate, transfer, or reason about—they are the physics of its world, externally imposed via MCTS. It operates within constraints but cannot model them.

In a paper first posted in 2022, Tony Wang, Adam Gleave, and colleagues demonstrated an even more dramatic limit (Wang et al. 2023): KataGo (an even stronger Go AI than AlphaGo, developed in 2019) could be beaten a whopping 97% of the time, by using AlphaZero-style training to find adversarial strategies which exploited how KataGo approached the game:

“Critically, our adversaries do not win by playing Go well. Instead, they trick KataGo into making serious blunders that cause it to lose the game.”

The KataGo team were able to mitigate this via adversarial training—that is, having KataGo simulate adversarial strategies during training and learn to respond to them—but only partially. Gleave’s strategies still worked 17.5% of the time even against adversarially trained KataGo; very impressive for playing Go badly!

These adversarial strategies were not arcane computer nonsense: a human expert could learn to use them to consistently beat superhuman Go AIs (and not just KataGo). Therefore, by Rocktäschel’s criteria, whilst Go AIs are “open-ended” relative to an unassisted human observer, relative to a human observer assisted by adversarial AI, they lack novelty in exploitable and learnable ways, and adversarial training only partially fixes this.

4.3 Does AlphaZero have phylogenetic understanding?

AlphaZero may disregard the human phylogeny of Go, chess, or etc., but via its self-play training loop, it creates and distills its own phylogeny: every move that it makes has a history in those millions of self-play games. Does this give it genuine understanding of the moves it makes, or merely an implicit grasp that falls short of understanding proper?

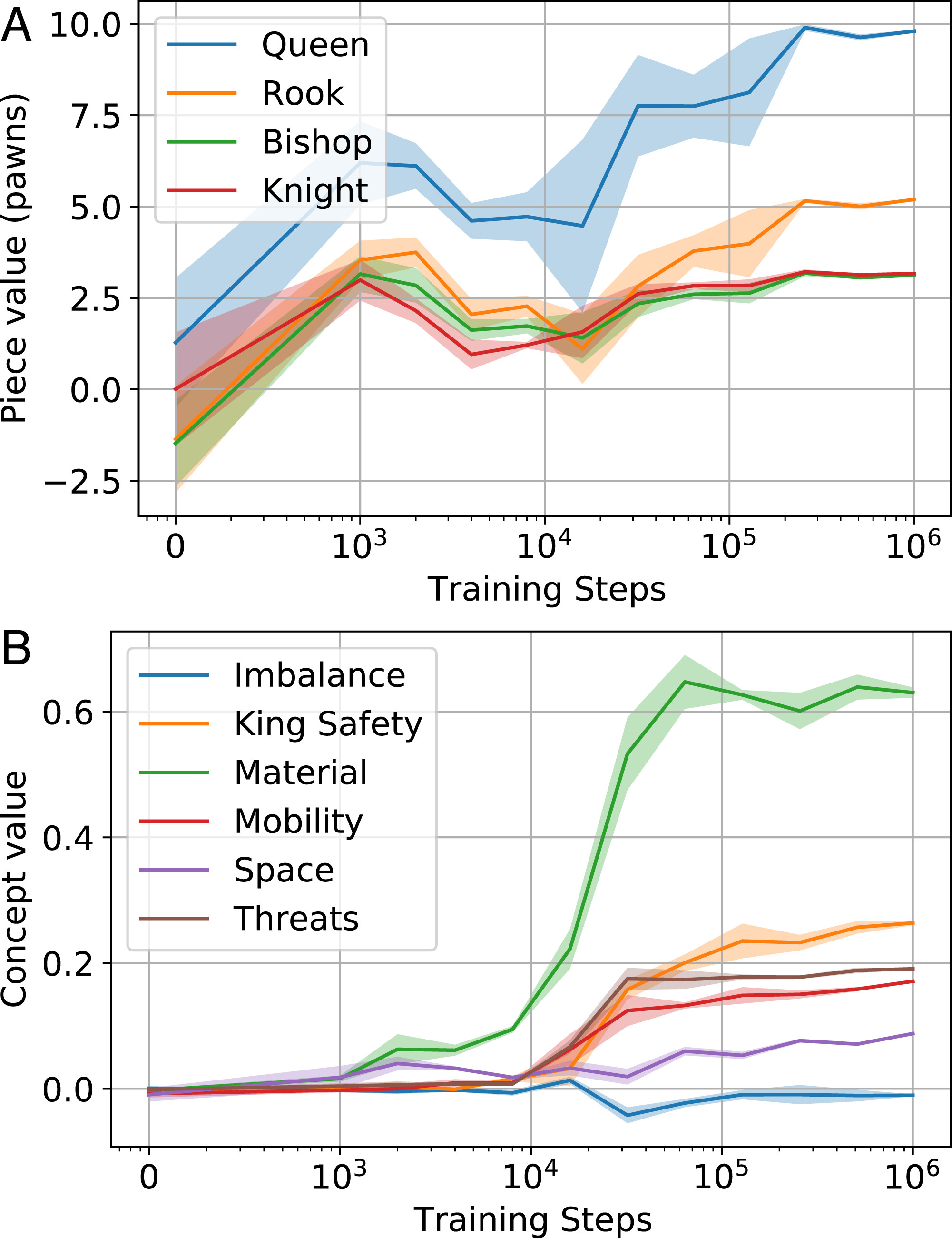

A 2022 DeepMind study investigated whether AlphaZero had learned to represent human chess concepts when learning to play chess. They defined a “concept” to be a function which assigns values to chess positions (e.g., the concept of “material” adds up the value of White’s pieces and subtracts the value of Black’s pieces). This notion was convenient, because such functions encoding many key chess concepts have been engineered to build traditional chess programs. Using a chess database, they then trained sparse linear probes to map the activations in AlphaZero’s neural network head to the functions expressing these concepts. They found that initially these probes all had very low test accuracy, but over the course of AlphaZero’s training they became much more accurate for many concepts, suggesting that AlphaZero was indeed acquiring representations of those concepts. For example, after hundreds of thousands of iterations AlphaZero eventually converged on the commonly accepted values for the chess pieces.

However, there are two key caveats to this result. First, this evidence is just from sparse linear probes, which are limited tools for interpretability. Second, defining chess “concepts” as functions conflates the positions those concepts refer to with what those concepts mean. Suppose that in all of the positions in the chess database used, in every position where someone was in check, there was never a 2x2 square all full of queens (a very rare pattern). Then both “being in check” and “being in check with no 2x2 square of queens on the board” would correspond to the same function, but obviously don’t mean the same thing.

As Fodor and Pylyshyn (1988) argued in their classic critique of connectionism—though we do not require the full compositionality they demanded (see the Postscript)—understanding these meanings requires grasping something of their systematic and compositional nature: if a system truly understands a concept, it should be able to recombine that concept with others in structured ways. Understanding “being in check” should be intrinsically tied up with understanding “being in check by a pawn”, “blocking a check”, “pinning a piece to the King” etc. The research does not explore such networks of interrelated understandings, and as such cannot demonstrate a deep abstract understanding of these concepts.

But is abstract understanding needed to understand chess (or Go)? Chess theory has increasingly favoured concrete explanations (see International Master John Watson’s Secrets of Modern Chess Strategy). Grandmaster Matthew Sadler’s 2025 article “ Understanding and Knowing” describes three levels of understanding of a position, each more concrete than the last. Concrete understanding means grasping the key variations—winning lines, refutations of alternatives, contrasts with similar positions—without exhaustive enumeration.

On these concrete terms, AlphaZero represents some progress, as it looks at far fewer positions than older chess systems in its search. However, it still looks at thousands of times more positions than a human grandmaster, so it will still explore many irrelevant lines. More deeply, it lacks counterfactual understanding—the grasp of not just what works, but why alternatives fail and how the analysis changes under different conditions. In the above Sadler article, a crucial piece of the highest level of understanding was seeing how (and why) the winning line in the position wouldn’t work in a superficially similar position. AlphaZero’s MCTS will never explore these sorts of counterfactual positions. The adversarial examples show that even in purely concrete terms, these systems can utterly fail to understand strange positions.

In summary, AlphaGo sits at the concrete level of our hierarchy of constraint adherence—between evolution’s physical adherence and modelled understanding, where constraints can be manipulated and transferred across contexts. Its representations are entangled rather than factored, so it cannot manipulate or transfer its implicit grasp of Go’s logic. Move 37 was a genuine creative discovery, but the concepts underlying it cannot be extracted and reapplied. In Boden’s terms, this is exploratory creativity within a fixed conceptual space, not the transformational creativity that would require learned, factored representations preserving their stepping-stone structure.

Stanley’s false-compass problem bites AlphaGo at both levels: the fixed win objective blinds it to stepping stones, and gradient descent on dense networks precludes the modular structure that transfer demands. More intelligence does not help when the objective itself is the problem—and so, despite their immense strength, these systems remain blind to deeper domain-general features, and can be bamboozled by spurious patterns even within their own domain.

But if AlphaZero still crushes humans, does domain-general understanding matter? It depends on what you want. AlphaZero is stronger than any human at chess—but would fail at “chess with one rule change” without retraining from scratch. Carlsen, though weaker, could adapt instantly, and would be very hard to bamboozle by playing badly! For robust generalisation to unknown unknowns, the deeper understanding matters; for raw performance on a fixed task, it may not. DeepMind’s work does suggest that AlphaZero learned to represent key chess concepts—but as we saw, this falls short of the modelled understanding that genuine creativity would require.

5 Putting the humans back in the loop

None of today’s AI systems—LLMs, LRMs, or AlphaZero—can, operating alone, handle the “unknown unknowns” that characterise human creativity.

But have we been asking the wrong question this whole time? So far, we have been focusing on whether AI systems, by themselves, can reason creatively. This framing echoes the dream (or nightmare, depending on who you ask) of fully autonomous AI systems, a dream infamously expressed by Nobel laureate Geoffrey Hinton in 2016:

“I think if you work as a radiologist you’re like the coyote that’s already over the edge of the cliff but

hasn’t yet looked down so doesn’t realize there’s no ground underneath him. People should stop training

radiologists now. It’s just completely obvious that within 5 years deep learning is going to do better than

radiologists because it’s going to be able to get a lot more experience. It might be 10 years but we’ve got

plenty of radiologists already.”

Geoff Hinton: On Radiology

History has not been kind to this prediction. But setting aside the inaccuracy of the timeline, notice how Hinton pictures deep learning as replacing radiologists, rendering them obsolete.

What if instead the future looks like radiologists and AI systems working together, to perform better than either could alone, or do radiology in more diverse settings? Then there might be a need for more radiologists than ever. Spreadsheets, after all, did not lead to fewer accountants.

CT and MRI scanners are expensive and immobile; sub-Saharan Africa has less than one MRI scanner per million people. AI-enhanced alternatives like photoacoustic imaging are cheaper and more portable—but still need radiologists to interpret them. If these techniques expand medical imaging across the developing world, global demand for radiologists could increase, not disappear.

In terms of creative reasoning, we should therefore be thinking not only about AI creativity, but also human-AI co-creativity. Consider coding and science; these are inherently interactive endeavours: any AI coder or scientist will inevitably interface with humans throughout. Who commissioned the software? Who are its users? Who will perform its experiments? To quote the AlphaEvolve authors from our MLST interview:

“I think the thing that makes AlphaEvolve so cool and powerful is kind of this back and forth between

humans and machines, right? And like, the humans ask questions. The system gives you some form of

an answer. And then you, like, improve your intuition. You improve your question-asking ability,

right? And you ask more questions. [...] We’re exploring [the next level of human-AI interaction] a

lot. And I think it’s very exciting to see, like, what can be done in this kind of symbiosis

space.”

Wild breakthrough on Math after 56 years... [Exclusive]

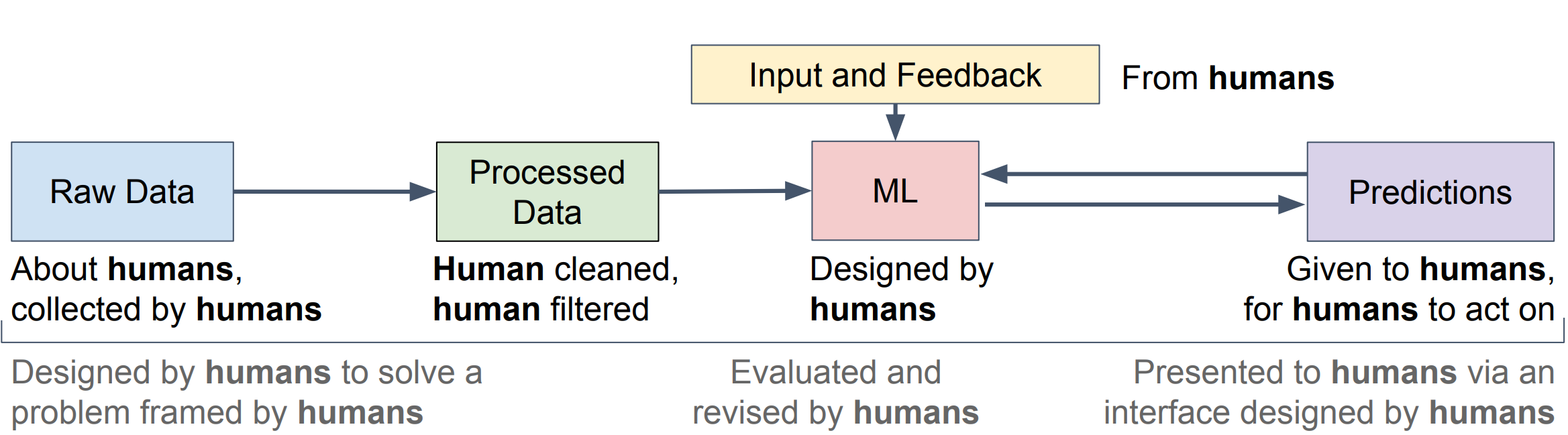

DeepMind researchers Mathewson and Pilarski show how humans are embedded throughout the machine learning lifecycle, from data collection to deployment. The Neuroevolution textbook echoes this too: “humans and machines can work synergistically to construct intelligent agents”, ultimately enabling “interactive neuroevolution where human knowledge and machine exploration work synergistically in both directions to solve problems”. We have so far been focusing on the “I” of AI, but the “A” often hides the extensive reliance of these systems on humans.

Consider the history. AlexNet’s 2012 breakthrough depended on ImageNet, whose 14 million labels required years of Mechanical Turk labour. ChatGPT’s self-supervised training consumed the internet (created by humans), and making it presentable required reinforcement learning with human feedback—relying on significant Kenyan labour.

Will AI always rely on human labour? Could not future AI systems be trained on AI-generated data and supervised by AIs, without any humans in the loop? Anthropic have after all been pioneering reinforcement learning with AI feedback, and the big tech companies have reportedly turned to synthetic data because they are running out of internet to train on. However, a 2024 front-page Nature paper (Shumailov et al. 2024) warned that indiscriminately training AIs on AI-generated data leads to “model collapse”—an irreversible disappearance of the tails (i.e., low-probability outputs) of the AI’s distribution. This would especially kill creativity, since losing the tail means losing unexpected and novel outputs. Human-AI collaborations can exploit complementary strengths: we often find generation harder than evaluation, whilst AI systems often demonstrate the reverse. Thus, by delegating tasks, such as in LLM-Modulo, one can get the best of both worlds. As Stanley argues, the human ability to recognise interestingness is irreplaceable:

“We have a nose for the interesting. That’s how we got this far. That’s how civilization

came out. That’s why the history of innovation is so amazing for the last few thousand

years.”

Prof. KENNETH STANLEY - Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned

5.1 What does human-AI co-creativity look like?

In 1997, Deep Blue beat chess world champion Garry Kasparov, and by 2006 computers had decisively overtaken human chess players: Hydra crushed Michael Adams 5½–½ in 2005, and Deep Fritz beat world champion Vladimir Kramnik 4–2 in 2006. (AlphaZero would later join the party with a bang in 2017.) As we saw, Go went the same way in 2016. Human-AI collaboration is now an integral part of high-level play in both games, with top players extensively preparing with computers. One might worry that this would atrophy these players’ creative minds, but quite the opposite seems true. After the advent of AlphaGo, human Go players began to play both more accurately and more creatively. This really kicked in when open-source superhuman Go AIs arrived, as people could then learn not only from their actions, but also from their reasoning processes.

A similar story is true of chess: not only do players play much more accurately now than in the past, but computer analysis helped overturn dogmatic ideas of how chess could be played, and breathed new life into long abandoned strategies. AlphaZero has been used to explore new variant rules for chess, dramatically faster than humans could alone. Most recently, in a 2025 paper DeepMind showed how chess patterns uniquely recognised by AlphaZero could be extracted and taught to human grandmasters, demonstrating that these systems can continue to enhance the human understanding of chess.

Beyond board games, Stanley’s Picbreeder (Section 2) remains the clearest case study: human selection plus machine variation produced vastly superior representations to anything SGD could reach alone.

In experimental science, it may be more important than ever to keep humans in the loop. At the 2026 World Laureates Summit, Nobel laureate Omar Yaghi described coupling ChatGPT with a robotic platform to crystallise materials that had defied the chemistry community for a decade.6 The human contributes thirty-five years of domain knowledge—reticular chemistry, the experimental scaffold, the judgement of what counts as “good crystallinity”. ChatGPT explores the parameter space within those constraints. Three experimental cycles yielded crystals three times more crystalline than a decade of unaided effort. AlphaFold follows the same logic: it predicts protein structures in minutes rather than years, but as AlphaFold’s lead developer John Jumper put it in our interview, “these machines let us predict. They let us control. We have to derive our own understanding at this moment.”

Both illustrate what prediction alone cannot reach. At the same Summit, optimisation theorist Yurii Nesterov articulated the limit: AI conclusions “can be related only to a model of the bird [i.e. the object being studied] which exist in the corresponding virtual reality. If the model is done correctly, then this conclusion can be used in real life. If not, it could be a complete nonsense.” And Turing Award laureate Robert Tarjan identified what no model can supply: “asking the right question is more important than finding the answer. To be a really great researcher, you have to develop a certain kind of taste.” Taste—the nose for the interesting—is what the human brings to the collaboration.

Human-AI collaborations may also soon be fruitful in academia. Or so argued Fields medallist Terence Tao in a 2024 interview for Scientific American. Inspired by the success of automated proof assistants like Lean, Tao imagines mathematicians and AIs soon working together to produce proofs:

“I think in three years AI will become useful for mathematicians. It will be a great co-pilot. You’re trying to prove a theorem, and there’s one step that you think is true, but you can’t quite see how it’s true. And you can say, ‘AI, can you do this stuff for me?’ And it may say, ‘I think I can prove this.’”

Tao sees this eventually transforming mathematical practice itself—from “individual craftsmen” to a pipeline “proving hundreds of theorems or thousands of theorems at a time”, with human mathematicians directing at a higher level and formalisation making explicit the vast tacit knowledge “trapped in the head of individual mathematicians”.

6 The Structure of Creativity

6.1 The Semantic Graph

LLMs, LRMs, AlphaZero—all of these display what we might call statistical creativity: they search through the space of possibilities, in training and at inference, and stumble upon interesting regions. But the heart of creativity is semantic—grounded not in statistical search but in understanding the structure of the domain, the phylogeny. As Tim put it in conversation with neuroevolution researcher Risto Miikkulainen (co-author of the Neuroevolution textbook we cited in the introduction):

“We are describing a kind of statistical creativity where we want to make it more likely that we will find these tenuous, interesting regions. But could there be a kind of almost pure form of creativity where we know the semantic graph?”

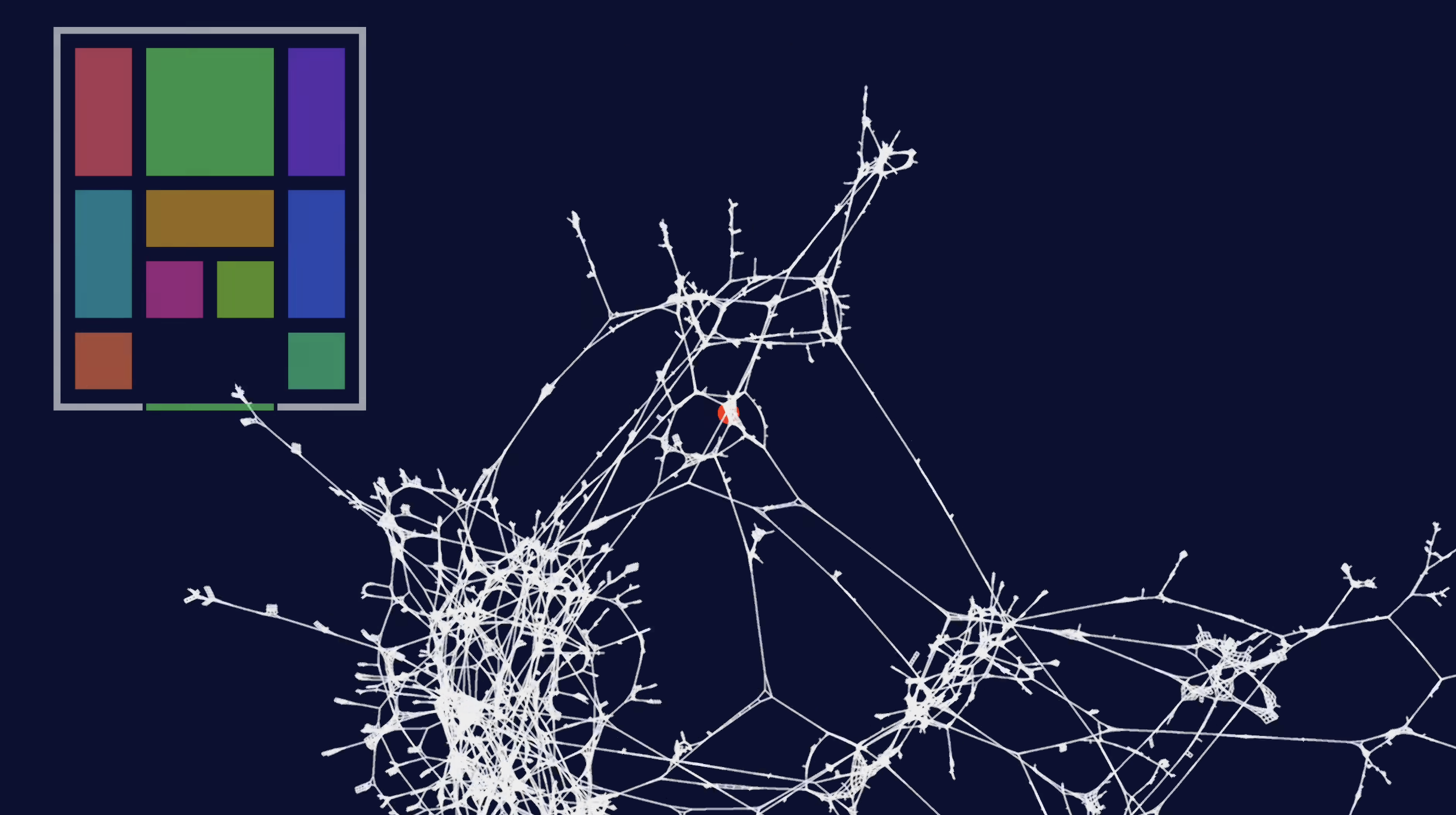

A powerful intuition pump for these “semantic graphs” is this beautiful visualisation by the YouTuber 2swap:

A semantic graph—not a knowledge graph in the NLP sense, but the full space of possibilities in a domain, with its own topology—is like this Klotski graph writ large. Particularly important are the intricate substructures—local regions with their own logic—connected by narrow paths. Semantic creativity is about traversing this semantic graph, discovering the logic of your local bubble, and finding those tenuous connections that lead to new substructures—new conceptual spaces. Stanley’s insight is spot on: in the semantic graph, discovering a new substructure literally “adds new dimensions to the universe”, opening up a new logic to explore. In real creative domains, of course, the graph is shrouded in a “fog of war”; we discover new dimensions and subspaces as we go, rather than navigating a known topology. As Miikkulainen put it when shown this visualisation: creativity involves “pushing into another area of kind of solutions that you’ve never seen before” by finding those rare transitions between substructures.

How can we measure this semantic creativity? Perhaps the answer lies in the size of the subspace discovered. The stepping stone that leads to a vast new region of possibilities is more creative than one that leads to a small cul-de-sac. Looking at the Klotski graph, we can immediately see which clusters are large and which connections are most valuable. But in the real world, this is all covered by the fog of war: it takes time to realise where our stepping stones will lead, or just how big a new subspace actually is. Only in retrospect, once the phylogenetic tree has been expanded by subsequent discoveries, can we recognise how extraordinarily creative (or not!) a stepping stone was.